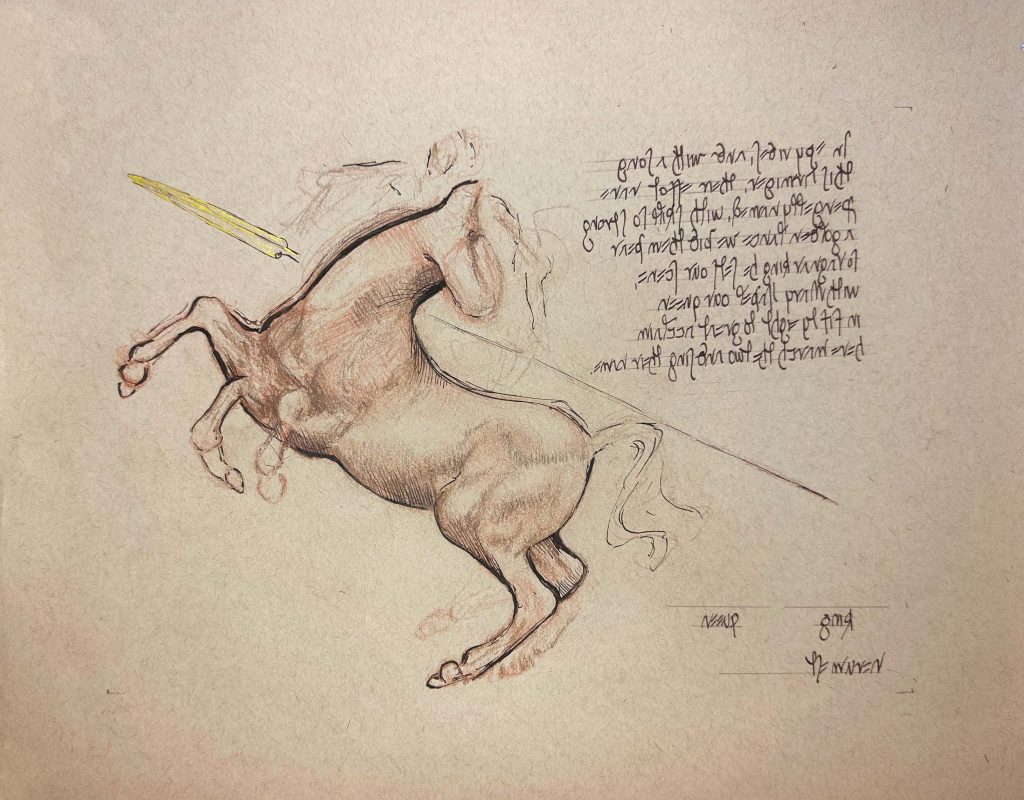

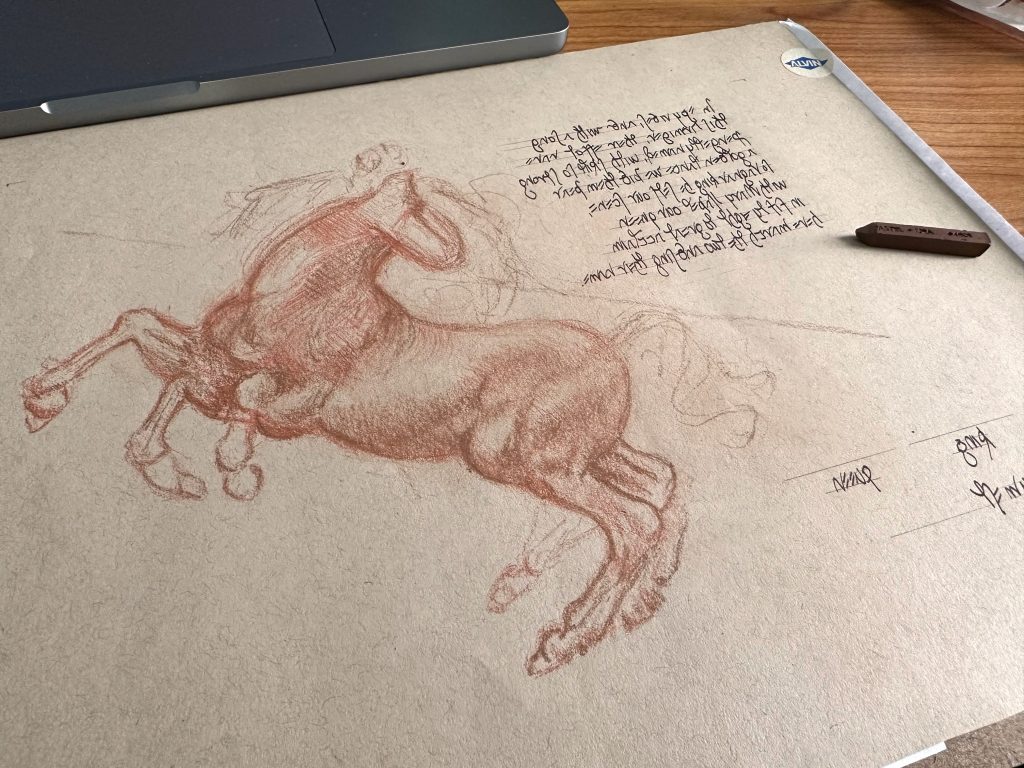

To my great delight, I was requested to make a Golden Lance award scroll for Epy Pengelly. So here it is in its gold-and-equine glory. All parts—rispetto-style verse, design, and art—by me.

In Epy rides, and with a song

this Armiger, their effort rare,

Pengelly named, with skill so strong,

a Golden Lance we bid them bear.

So Ragnar King he sets our scene,

with Mary Isabel our Queen,

in Fifty Eight to great acclaim

here March the two and sing their name.

giddy up

Leonardo da Vinci. This man sketched…a lot of horses.

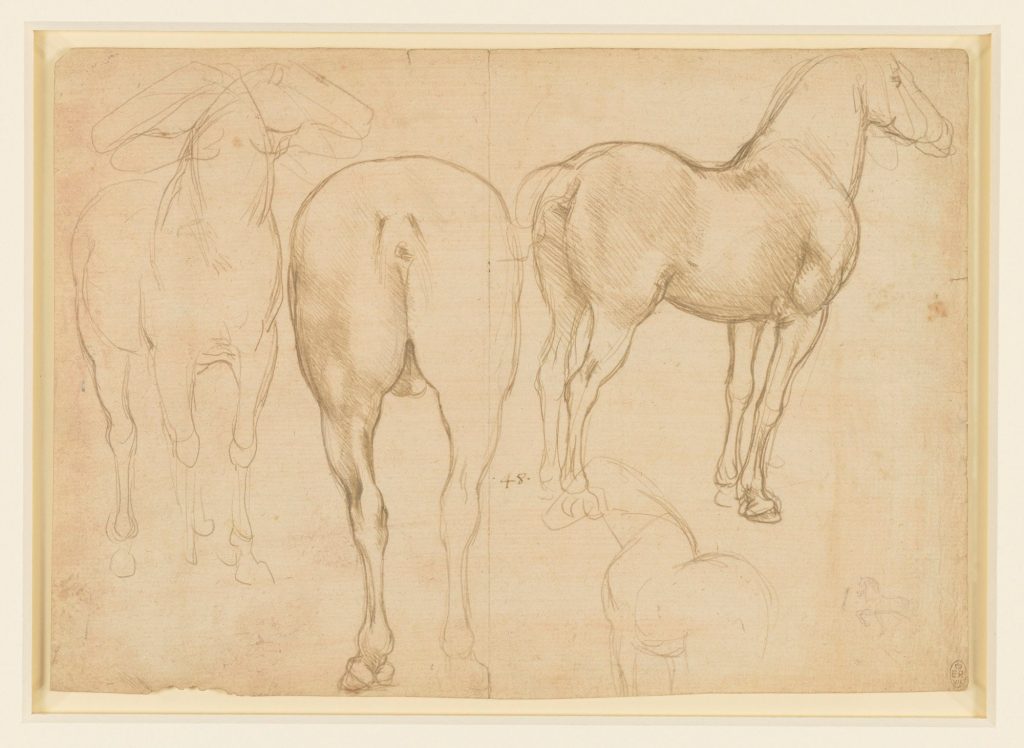

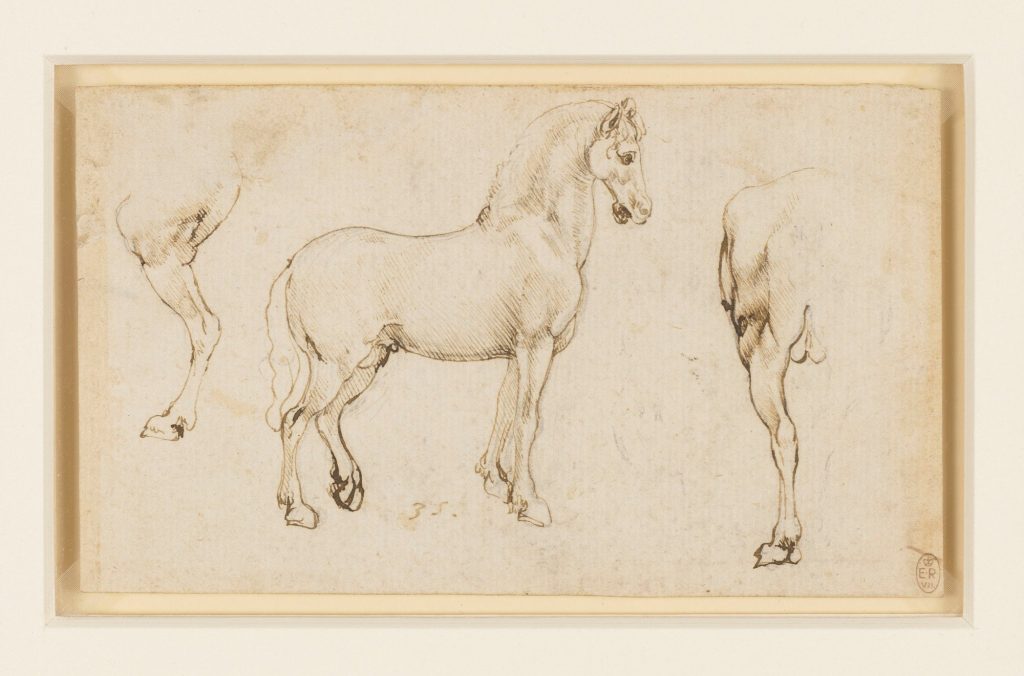

Horses standing.

Horses rearing.

Horses jumping.

Horse heads, horse legs, horse butts.

In the 2004 art book, “Leonardo da Vinci: Sketches and Drawings” there is an entire chapter dedicated to the subject, with 26 images of horses included1. The 2019 Royal Collection Trust exhibition “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing” featured 222. In his chapter within the former, Johannes Nathan writes about the importance of horses in the Renaissance, including (or especially) due to their use in warfare. Leonardo was fascinated by exploring warfare, expecially its emotion3. The rendered battle between horsemen in the background of the Adoration of the Magi demonstrates his enthusiasm.

But this fascination is only part of the picture.

THE BACKGROUND

disegno

Let’s set the scene.

In 15th–16th century Italy there was an emphasis in draftsmanship, an approach which held that good drawing was the root—not only of all quality artistic endeavor, but of measuring the world4. In part, this emphasis existed due to the growth of Renaissance humanism, which looked to the ancient world for examples of how to live and how to reconcile religion with the changing world, and in so doing reorient humanity within the cosmos5. Humanism was a perspective through which artists would explore nature through their art, and draftsmanship (disegno in Italian) was the first step. (I have a lot more to say about Humanism in my post about Kolfinna’s scroll6.)

In his “Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects”, noted artist, groupie, and early modern hype man Georgio Vasari writes “This disegno, when it brings forth a creative idea from our critical faculty, requires a hand ready and able, thanks to years of study and practice, to draw and to express well whatever thing Nature has created, with a pen, a stylus, a charcoal stick, a pencil. . . .7” In this atmosphere, Leonardo would have been well trained in disegno.

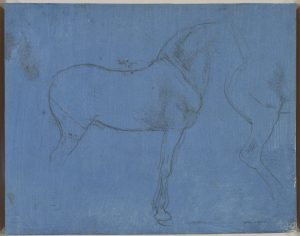

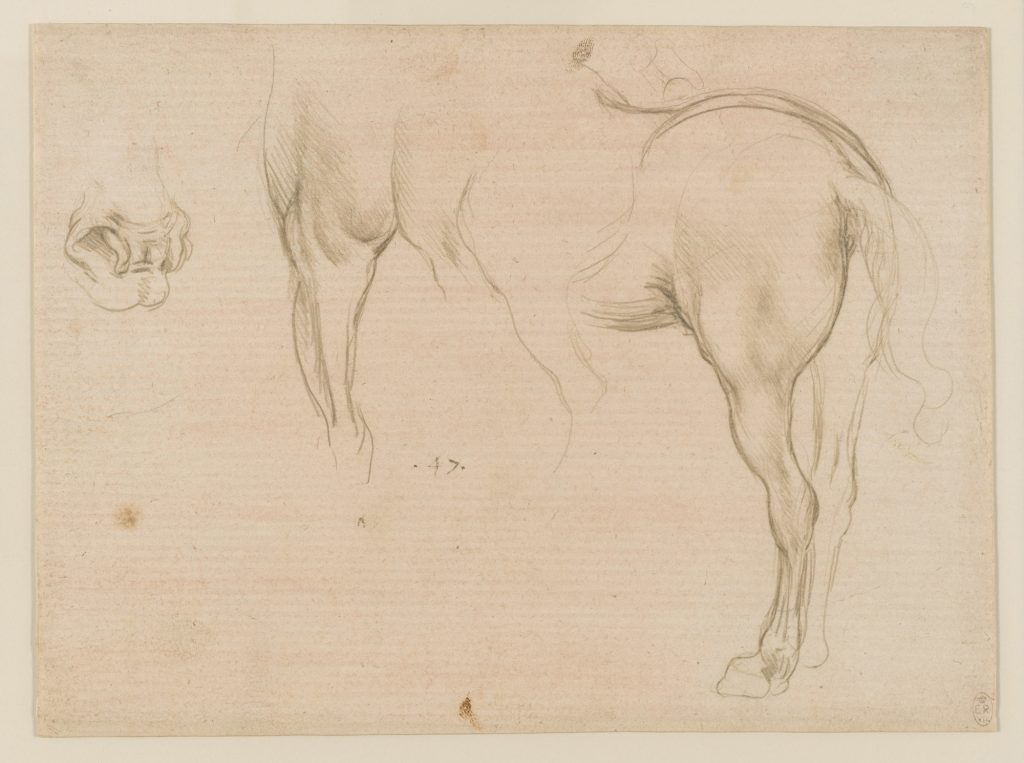

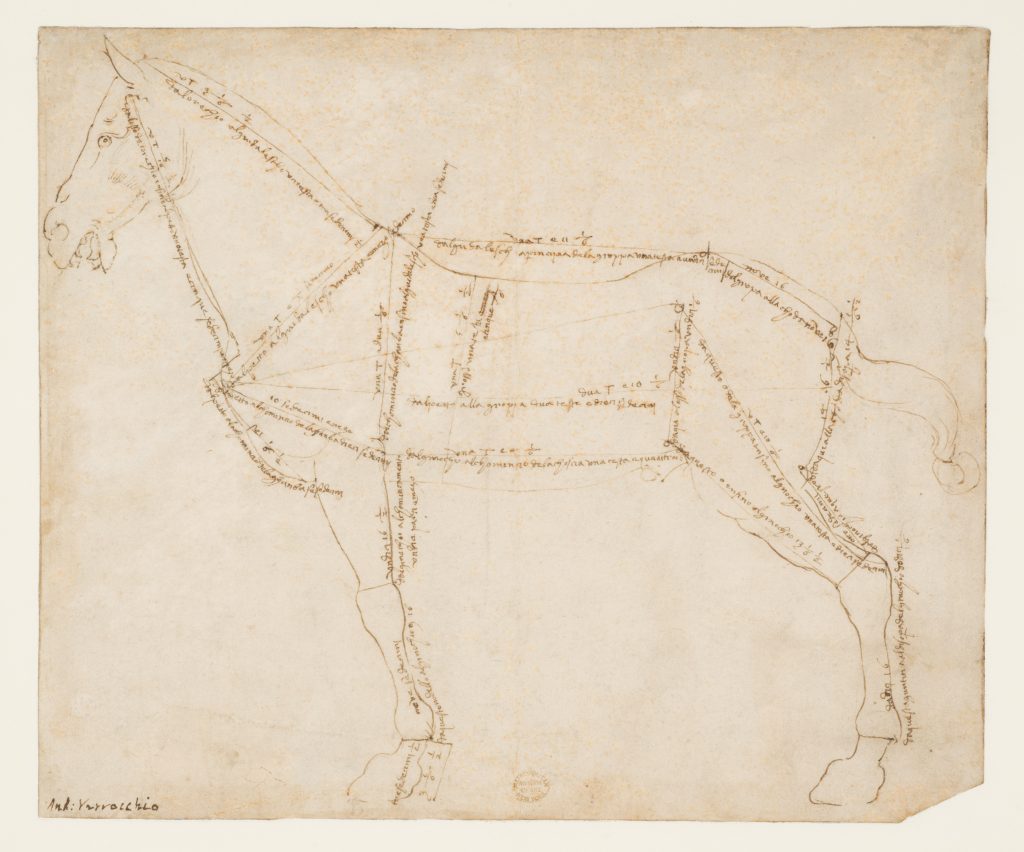

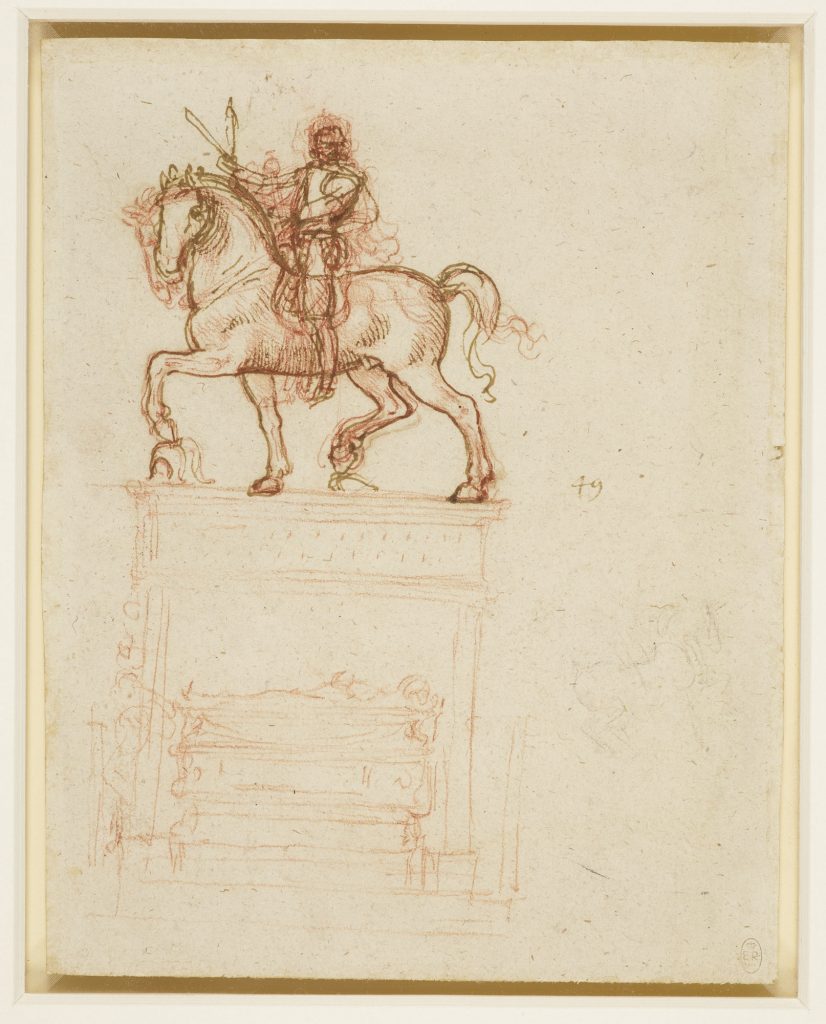

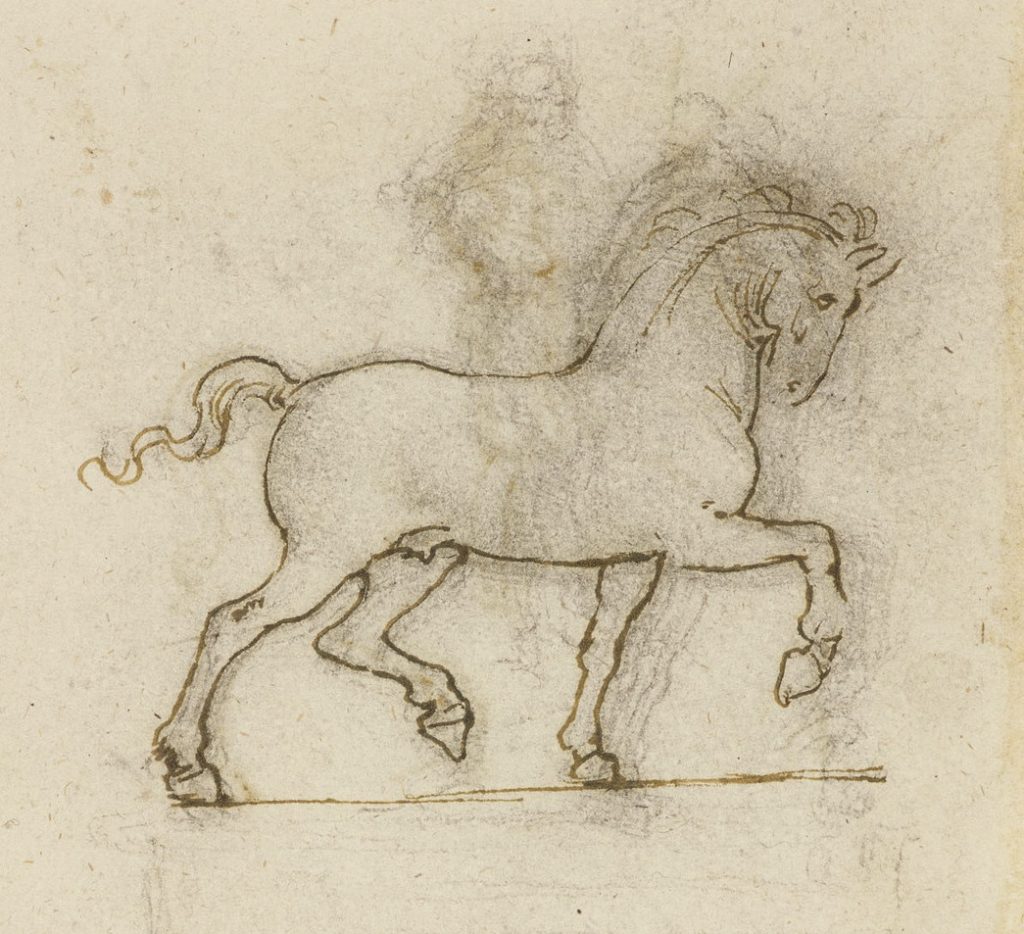

Studying the form with measurements and scientific principles was part of his and many others’ practices. The horse at right, drawn by Leonardo’s master Andrea del Verrocchio, possibly as preparation for a bronze equestrian statue, is a perfect example. (Compare it with a similar drawing of a horse in profile by Leonardo, below.)

When I started this project, I didn’t have the right context. Based on his modern reputation, I “knew” that Leonardo was as an artistic genius who combined art and science. I “knew” his legacy lie in observation, measurement, and technical expertise, and I “knew” that he drew to invent and discover his world. And due to the concept of disegno, I knew he would have made these explorations through drawing.

So when I first began researching this scroll, I assumed that the preponderance of horses was merely due to his study of the animals for anatomical purposes—for an exploration of truth, in the High Renaissance humanist vein. Exploration without intention. After all, this is a man who dissected cadavers to learn anatomy. I had bought hook, line, and sinker into the story of Leonardo-as-genius that has come down to us from Vasari through successive generations, all of whom put their own spin on his biography for their own reasons.

In the process of researching, however, I learned that this story is misleading.

In 1482 Leonardo was commissioned to create a monument in honor of the late Duke Francesco Sforza. It was intended to be greater than life size, and the technical logistics of potentially casting such a large figure in one piece with the lost wax method entranced Leonardo so much that the commission dragged on and on. He had gone so far as to make a twenty-four foot tall terracotta model, but…

The work was never finished8.

In 1505 Leonardo began “The Battle of Anghiari”, a huge wall painting (54 x 21 ft) in the Sala dei Cinquecento, used by the Medicis as a reception room. (His rival Michelangelo was supposed to paint the opposite wall, but since Leonardo’s side had better light, he didn’t want to be shown at a disadvantage.) According to his diary the weather turned when he was just beginning, ruining the cartoon (the full-size paper template used by wall- and fresco-painters to transfer their designs) and the conditions, so…

The work was never finished9.

In 1506 Leonardo returned to Milan to begin work on a commission by Sforza’s greatest rival, Gian Giacomo Trivulzio, for an equestrian funerary monument, a commission secured largely on the back of renown from the unfinished Sforza monument listed above. This new monument was based on the initial drawings for the Sforza horse, but also included tomb decoration. We’re aware of the commission only through financial documents and sketches, because—whether through political machinations or personal issues, and…

The work was never finished10.

Even the treatise On Painting was a work in progress when his mortal clock ran out11. Fundamentally, in spite of touting himself as a sculptor when he sold his services to elite patrons, we have zero uncontested proof of finished sculptures12.

This knowledge granted me two gifts.

gift one: i’m not leonardo

First, I learned that my initial apprehension at using an exemplar by Leonardo was, perhaps, misplaced. Rather that having to beneficently grant myself grace for not emulating his results perfectly due to our vastly different training and situations—the “oh, but he’s Leonardo da Vinci, how could I ever match him” mindset—I developed a clearer picture of as Leonardo as a flawed and relatable human, and this allowed space for both of us to embody our own creative styles with equal validity.

For instance, as discussed above I learned that our friend Leonardo had a real lack of follow-through. The reasons for this are debated. Perhaps he preferred to research and prep and plan, in the Italian Renaissance distinction of “concetto” vs “mano”13 (which, as I settle into middle-age, I find relateable). Perhaps it was a result of stifling perfectionism (with his history as a recognized young talent, I wouldn’t be surprised #giftedkid). Or perhaps—as at least one art historian has suggested—he had ADHD14.

Whatever the reason, we are left with a lot of sketches of horses, a lost treatise on their anatomy, and no finished sculptures. The hype created by Vasari has developed into a fiction of perfection, of untouchability. But knowledge punctures this lionized myth.

gift two: context

And secondly, research uncovered the context of many of these horse sketches.

They weren’t created purely for artistic discovery, theoretical as some physics. I already mentioned briefly that Leonardo was fascinated by emotion and warfare and this translation through horses. But the context is pragmatic: they were made as preparatory drawings for further artwork like murals, paintings, and sculptures. They were created in pursuit of something more tangible.

(And they would have been. If he’d have finished them.)

And this makes a lot of sense to me, a 20th–21st century artist. After all, doing ample prep drawings was something I was taught in school, too. Counter to the popular notion of Leonardo exercising his artistic genius just for the sake of itself, he was doing it precisely for the same reason I would do it. Alongside the revelation that Leonardo was just as prone to dropping a project as any number of neurodivergent artists venting about executive dysfunction on TikTok, was the reminder that his training emphasized being prepared as well.

With these two new humanizing nuggets of knowledge buoying me, I could lean further into creation without feeling beholden to Leonardo’s legacy.

THE FIGURES

Human though we both might be, there are definitely some difference between us.

Leonardo da Vinci was surrounded by horses from birth.

I was not.

Leonardo da Vinci was working in the workshop of a master artist by the age of 14.

I was not.

Leonardo da Vinci was a master in a guild of artists and doctors by the age of 20.

I was not.

What I do have is 40-some-odd years’ of experience with dry media, and a pretty engrained sense of my own style. So I tried to respect Leonardo’s while being true to my own. Leonardo’s objective was an expression of equine form in preparation for a sculpture. Mine was an award. I’m not here to make copies; I’m here to make art in celebration of my friend.

neigh? yay!

At right is the primary sketch on which I based my scroll.

According to the museum record15, this horse was done as a preparatory drawing for Leo’s forthcoming mural of The Battle of Anghiari in the Great Council Chamber of the Palazzo della Signoria in Florence. As I listed above, whether due to melodramatic weather or his own proclivities he never finished it, and about 60 years later Georgio Vasari himself was commissioned to complete the painting16. Still, Leonardo’s prep work remains for us to explore.

Its rendering style is not quite the Mannerist art of a century later, a technique developed by followers of Michelangelo which exaggerated musculature toward unreality. (One artist said another’s Hercules looked like “a sack full of melons”17, which I find particularly entertaining; I’ve always described Michelangelo’s “anatomy” as a sack full of bowling balls. (Cellini? I’m with you on this.)) But Leonardo’s horse is definitely a progenitor of that style, with the rippling definition of its thighs and knobbliness of its joints. I did my best to communicate the same anatomy, but at some point the texture and color of the chalk and my deep dislike of trapped bowling balls got the best of me, and I declined to attempt a 1:1 replication in lieu of something more true to myself and the scroll I was creating.

so sketchy

Leonardo could not have drawn this figure, as it stands, from life18. Far from a static pose, the twist indicates motion and emotion, and could only have been assembled from separate elements. The rear legs are planted, but Leonardo is trialling various front legs to create the desired effect. He frequently worked this way; we have early examples of primary sketches in silverpoint made more solid with pen and ink, and later sketches of chalk followed by ink. Delicate alternates of position laid out in less-definitive media and finalized with permanence.

Then as now, these quick sketches were common. Called “primo pensiero” (first thought) or “scizzo” (quick) sketches19, in my experience they can function anywhere from a visual brainstorm, to a visual experiment, to a demonstration of a plan. Subsequent sketches can help build up toward increasingly final renders, as we see in situations where Leonardo switches medium from charcoal to ink.

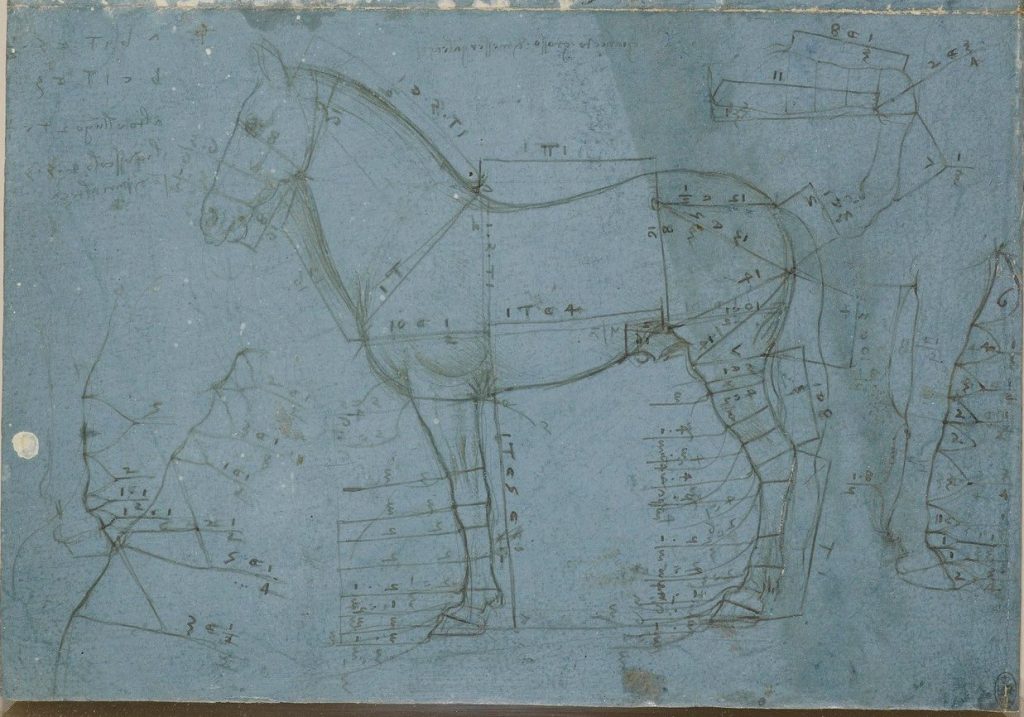

His drawings for the Svorza monument, the greater-than-life-size bronze horse statue described above which he designed but never finished, likewise show an iterative style which relies upon small changes as well as large20. Based on the similarity of the multi-legged sketches, it seems reasonable to deduce that his aim was to assemble a figure which met all of his needs. While these needs are naturally going to be different than those of a massive, single lost wax sculpture, still Leonardo was cognizant of the shape of the figure in space, as well as that space within the picture frame.

alert the media

Our pal Leo had access to a specific color of red chalk which I do not21. I’d wanted a chalk that matched the precise color he’d used (not pastels, since the museum record specified chalk—which is far more prevalent than pastels, especially at this early date22—and I wanted to respect that) and which offered the contrast and clarity he developed. And when I couldn’t source one, instead I blended together a few different colors of chalk, aiming at a similar result.

But I could elevate the chalk rendering with a second layer—a common technique at this place and time.

There is a pair of drawings of his, a rendering dated to c.1510–12 and another on the reverse of that same folio dated to c.1517–18, which appear to be a preliminary plan for two separate equestrian monuments—neither of which he completed23. Both drawings consist of a chalk base underneath a very loose sketch of a horse in ink. I really like how the first one in particular combines the definition of mass communicated by the chalk, with the energy and outline described by the ink.

My result is a layer of red-brown chalk beneath a dark brown ink sketch, a ghostly lancer mounted on an emerging animal, aimed toward a flash of gold.

sharp composition

A horse is a horse (of course of course), but this award required representation of what it is: a golden lance.

The sketchy indication of a rider from my exemplar could easily be armed. So I just needed an appropriate weapon. What I decided on is no invention; it’s a loose depiction of a 15th century lance currently held at The Met, indicated by light lines of ink and highlighted in gold. I think it does precisely what it needs to, without being overly rendered.

As a bonus, the diagonal line enhances the composition, drawing the eye down toward the signatures with a dramatic and definite slash, as if to say: it is done.

THE WORDS

could be verse

I’ve gotta be honest: I’m not a poet. My poetry experience is limited to an unusual amount of recreational sonnet-making and not much else. (Ask me sometime about all the ones I wrote as metatextual webcomic response back in the day, all of which have—for better or worse—been lost to time.)

But Epy isn’t only an equestrian, they’re also a musician. In fact, they play early music, and they’ve even arranged and recorded a multitrack/multi-instrumental song to perform with on their horse. So rather than write a simple scroll text, I wanted to write one and set their word fame to verse.

I chose a rispetto.

A rispetto is verse form from 15th century Tuscany consisting of two quatrains, with the rhyme scheme abab / ccdd24. Descriptions of its meter vary; some sources say tetrameter, some say pentameter, and some say hendecasyllabic. As far as I can tell, this discrepancy appears to be related to language and time period, and can be somewhat unpicked by its development.

Originally, the Tuscan rispetto was poetry of the people, a verse form based upon the octave, whose cousin became the sonnet25. Both of these are pentametric in English and hendecasyllabic in Italian26. This descrepancy is logical; different meters lend themselves more easily to different languages due to their natural rhythms. With my limited Italian, I can easily see why the odd-numbered syllable at the end of a line might suit. And iambs apply easily to the rhythms of spoken English, which makes iambic pentameter a natural choice for its sonnets and octaves.

That being said, the earliest rispetto in English that I could find is George Gascoigne’s (1535-77) six stanza poem “The Lullabye of a Lover”, which uses tetrameter27.

Sing lullaby, as women do,

Wherewith they bring their babes to rest,

And lullaby can I sing too

As womanly as can the best.

With lullaby they still the child,

And if I be not much beguiled,

Full many wanton babes have I

Which must be stilled with lullaby.

His verse that sounded to my ears less polished than an iambic pentametrical sonnet. Less studied, and more natural. More like the extemporaneous poems that the originals were said to be. (The original octaves could be performed by dueling poets, like early modern rap battles28.) So when I wrote Epy’s poem, I chose a quadrameter. I think it’s fitting that when the verse was read in court, it sounded playful, skipping and light, sing-song like a child’s poem.

It didn’t sound like deep literature. It sounded like joy.

In terms of content, I found various sources which discussed the different forms of love which the rispetto might evoke, and different moods and environments the rispetti might describe. (Sometimes literal environments; nineteenth-century poet Augusta Webster wrote, among others, rispetti using imagery of rivers, the four seasons, and fisher folk on a beach.29) But most inspiring to me in this situation was Theodore Watts Dunton’s 1881 sonnet—again, evolutionarily very similar to the rispetto—in which he “which presented the idea of the sonnet as being made up of two parts which are linked together like the flow and ebb of a wave. According to this model, the octave of the sonnet presents a thought and the sestet goes on to make a comment upon some aspect of this thought30.

I liked this idea instinctively, because it allowed the form of the poem to be reflected in the meaning. As such, I constructed my verse in two parts. The first,

In Epy rides, and with a song

this Armiger, their effort rare,

Pengelly named, with skill so strong,

a Golden Lance we bid them bear.

sets up this theoretical moment. Epy approaches the scene or the court, riding in appropriately armed, laden with name and honoriffic. Then follows the second half, the ebbing of the wave:

So Ragnar King he sets our scene,

with Mary Isabel our Queen,

in Fifty Eight to great acclaim

here March the two and sing their name.

As the wave ebbs, it drops upon the sand the story of the king setting the scene, partnered by his queen. The requisite date of the scroll text is snuck in with doubled meaning, as “March the two” serves both as a verb-and-noun phrase as well as a date: the second of March, AS 58.

I have aeons of experience with pentameter, but one foot less in meter somehow equates to more than a foot of meaning. The constraints required me to be a bit acrobatic with the language, which was both fun to craft and elicted a more playful result, which rather matches the bouncing feel of the rhythm. I wouldn’t be surprised if I added rispettos to my repertoire in future. They’re quite fun to write.

script

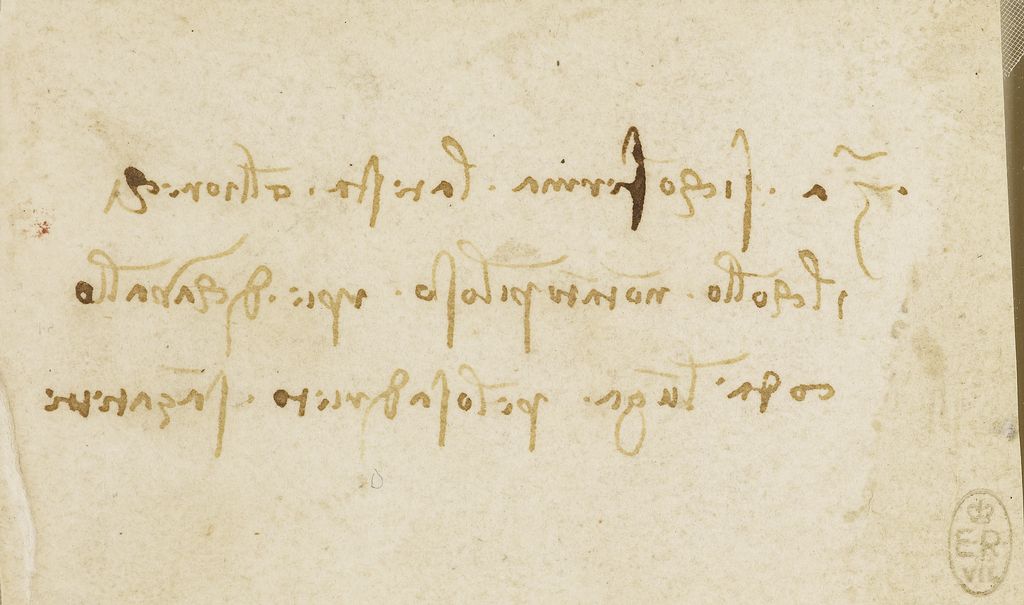

The script is based on Leonardo’s famous “mirror writing”.

Ordinarily I select characters from exemplars myself to assemble a script (often using a visual research application called Tropy31), but Kolfinna offered her previously-extracted ductus compilation

so I didn’t have to reinvent the wheel32. One upside to using a famous artist as an exemplar is that using someone’s ductus can save me a lot of time.

The big downside is that it meant I failed completely to take into consideration the proportions of Leonardo’s handwriting, the x-heights and ascenders and descenders and typical interlinear spacing. It changes the final look, but as I’ve previously mentioned: this is an homage, not a copy. And as I’ve also previously mentioned: I’m not a forger. Fundamentally this is my hand’s version of Leo’s hand.

For whatever reason, I find reading and writing backward quite easy, so I had fun with that part, too.

THE RESULT

why art history?

I entered into this project with the same overawed impression of Leonardo Da Vinci as lives in the popular consciousness. But it turned out there was a palpable gulf between what I thought I knew about Leonardo, and what researchers currently think. And doubtless if I continue to research him for this or other projects (which seems likely), I will learn even more and gain more context.

I’m neither Leonardo, nor a 19th century student on the Grand Tour. I’m a modern person with a specific goal. In attempting to copy one of his sketches 1:1, I would have done both myself and that goal a disservice. If i’ve learned anything over my decades of making art, it’s that each piece has its own objective, and no matter the goal of my reference, it’s best to keep the context of my own work in mind.

This proves the worth of researching the context of the art we emulate. If I hadn’t delved in, I would have tried to sublimate my style, diminishing myself. I would have simply tried to replicate a Leonardo horse sketch without asking why there were so many to choose from. And if I hadn’t asked why there were so many, I wouldn’t have learned about his intention to create his mural and his full-size sculpture. If I’d simply copied, I wouldn’t have this new picture of who Leonardo actually was as an artist, cleared slightly of the mythos created by Vasari, history, and Leonardo himself. I wouldn’t have learned about his lack of followthrough, or asked hard questions about reputation, self-advertisement, legacy, and “genius”.

And I wouldn’t have felt such relatability for someone with a cartoon turtle named after him.

above all

It was a particular pleasure to be asked to create this scroll for Epy, to honor my friend with artwork and words. I’ve known them for a number of years; we live in the same camp at Pennsic, and even before they moved in, we lived in the same neighborhood. So I’ve had ample opportunity to witness just how damn hard they work. The award—one of very few Golden Lances granted in Atlantia—was long in coming and is well-deserved.

NOTES

- Frank Zöllner, ed., Leonardo Da Vinci, 1452-1519: Sketches and Drawings (Taschen, 2000) 26–39. ↩︎

- “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing,” Royal Collection Trust, 2019, https://www.rct.uk/collection/exhibitions/leonardo-da-vinci-a-life-in-drawing. ↩︎

- Johannes Nathan, “Studies for equestrian monuments and horses”, in Leonardo da Vinci: Sketches and Drawings, ed. Frank Zöllner (Taschen, 2004), 26. ↩︎

- Noah Charney and Ingrid Rowland, The Collector of Lives (WW Norton, 2018), 42, Apple Books. ↩︎

- Sharon Bailin, “Invenzione e Fantasia: The (Re)Birth of Imagination in Renaissance Art” Interchange 36, no. 3 (September 2005): 261. ↩︎

- “Kolfinna’s Laurel”, posted February 19, 2023, https://mydwynterstudios.com/kolfinnas-laurel. ↩︎

- Translated in Charney and Rowland, Collector, 46. ↩︎

- Charney and Rowland, Collector, 197. ↩︎

- Charney and Rowland, Collector, 5–6. ↩︎

- Emily Hanson, “Inventing the Sculptor: Leonardo Da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth” (MA thesis, Washington University in St Louis, 2012), 50–51, https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/765. ↩︎

- Robert Wallace, The World of Leonardo, 1452-1519 (Time-Life Books, 1975), 57, http://archive.org/details/worldofleonardo100wall. ↩︎

- Hanson, “Inventing”, 1. The “Budapest Horse” is possibly his, though its attribution is still being debated. See Zoltán Kárpáti, Leonardo Da Vinci and the Budapest Horse and Rider. (Museum of Fine Arts Budapest, 2018), https://www.academia.edu/37830649/Leonardo_da_Vinci_and_the_Budapest_Horse_and_Rider. ↩︎

- Hanson, “Inventing”, 47. ↩︎

- Charney and Rowland, Collector, 192. ↩︎

- “A Rearing Horse”, Royal Collection Trust, https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/31/collection/912336/a-rearing-horse. ↩︎

- Charney and Rowland, Collector, 9. ↩︎

- Charney and Rowland, Collector, 3–4. ↩︎

- Nathan, “Studies”, 26. ↩︎

- “Preparatory drawing during the Italian renaissance, an introduction”, Khan Academy, https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/renaissance-reformation/high-ren-florence-rome/beginners-guide-high-ren/a/preparatory-drawing-during-the-italian-renaissance-an-introduction. ↩︎

- Hanson, “Inventing”, 35, as well as many visible examples. ↩︎

- “Chalk”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/about-the-met/collection-areas/drawings-and-prints/materials-and-techniques/drawing/chalk. ↩︎

- “The Eighteenth-Century Pastel Portrait”, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, September 2010, https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/papo/hd_papo.htm. ↩︎

- “”Recto: A study for the Trivulzio monument. Verso: A study for an equestrian monument”, Royal Collection Trust, 2019, https://www.rct.uk/collection/search#/41/collection/912356/recto-a-study-for-the-trivulzio-monument-verso-a-study-for-an-equestrian-monument. ↩︎

- P. Caruana Dingli, “Rispetti and sonnets: the Anglo-Italian context of Augusta Webster’s later poetry (1881-1893).” Journal of Anglo-Italian Studies 5 (1997): 127–128. ↩︎

- Dingli, “Rispetti and sonnets”, 127–129. ↩︎

- For the octave form, see Giovanni Kezich, “Extemporaneous Oral Poetry in Central Italy.” Folklore 93, no. 2 (1982): 194; for discussion of Chaucer’s first translation of a Romance language form to iambic pentameter in the late 1370s, see Martin J. Duffell, “‘The Craft So Long to Lerne’: Chaucer’s Invention of Iambic Pentameter.” The Chaucer Review 34, no. 3 (2000): 271. ↩︎

- “The Lullaby of a Lover”, Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/56369/the-lullaby-of-a-lover. ↩︎

- Kezich, “Extemporaneous Oral Poetry”, 195. ↩︎

- Dingli, “Rispetti and sonnets”,131–133. ↩︎

- Dingli, “Rispetti and sonnets”,134. ↩︎

- “Tropy”, https://tropy.org. ↩︎

- “Ffernfael of Carleon: Master of Defense Scroll”, Meisterin Kolfinna Valravn, June 3 2023, https://sites.google.com/view/kvalravn/scribe/2023/04-mod-ffernfael-of-carleon. ↩︎

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bailin, Sharon. “Invenzione e Fantasia: The (Re)Birth of Imagination in Renaissance Art.” Interchange 36, no. 3 (September 2005): 257–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-005-6865-3.

Caruana Dingli, P. “Rispetti and sonnets: the Anglo-Italian context of Augusta Webster’s later poetry (1881-1893).” _Journal of Anglo-Italian Studies 5_ (1997): 125-142. https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/82677.

Charney, Noah, and Ingrid Rowland. The Collector of Lives. New York, NY: WW Norton, 2018. https://books.apple.com/us/book/the-collector-of-lives-giorgio-vasari/id1215382287.

Duffell, Martin J. “‘The Craft So Long to Lerne’: Chaucer’s Invention of Iambic Pentameter.” The Chaucer Review 34, no. 3 (2000): 269–88.

Griswold, William, and Linda Wolk-Simon. Sixteenth-Century Italian Drawings in the New York Collections. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994.

Hanson, Emily, “Inventing the Sculptor: Leonardo da Vinci and the Persistence of Myth”. MA thesis, Washington University in St. Louis, 2012. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/765.

Kárpáti, Zoltán. Leonardo Da Vinci and the Budapest Horse and Rider. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 2018. https://www.academia.edu/37830649/Leonardo_da_Vinci_and_the_Budapest_Horse_and_Rider.

Kezich, Giovanni. “Extemporaneous Oral Poetry in Central Italy.” Folklore 93, no. 2 (1982): 193–205.

Kemp, Martin. “From Mimesis to Fantasia: The Quattrocento Vocabulary of Creation, Inspiration and Genius in the Visual Arts.” Viator 8 (January 1977): 347–98. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VIATOR.2.301573.

Maurino, Ferdinando D. “Italian Popular Poetry: Origin and Definition.” Journal of the Folklore Institute 7, no. 1 (1970): 36–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/3814230.

“The Project Gutenberg eBook of Lives of the Most Eminent Painters Sculptors & Architects, Volume IV. by Georgio Vasari.” https://www.gutenberg.org/files/28420/28420-h/28420-h.htm.

Tristano, Richard M. “‘In the Guise of History’: History and Poetry in Cinquecento Italy.” Viator 44, no. 3 (September 2013): 369–95. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.VIATOR.1.103489.

da Vinci, Leonardo, and Jean Paul Richter. The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci. Courier Corporation, 1970.

Wallace, Robert. The World of Leonardo, 1452-1519. Time-Life Books, 1975.

Zöllner, Frank, ed. Leonardo Da Vinci, 1452-1519: Sketches and Drawings. Taschen, 2000.