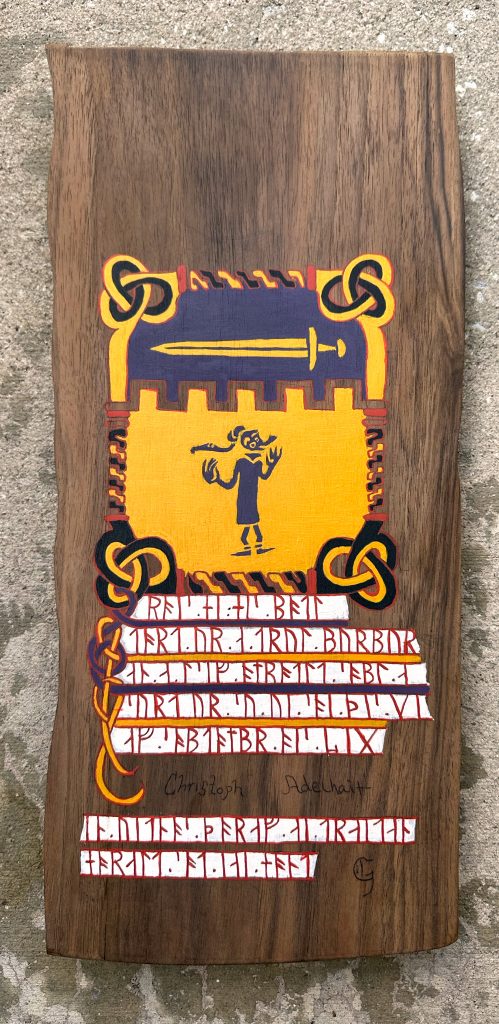

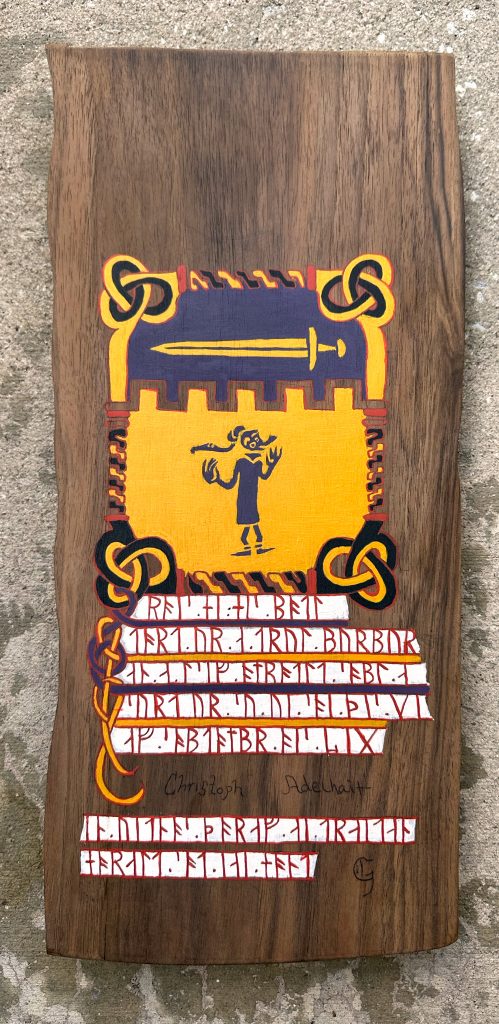

I was honored to be asked to create a scroll on the occasion of Sir Skinna-Steinarr’s elevation to the chivalry. Words and wooden scroll by me.

Christoph King and Adelhait Queen had these runes carved to praise Skinna-Steinarr,

Þegn of strength and honor, warrior of the weapon-meeting.

Mark this day with a golden chain, and name him kappi.

Raise high his battle standard Or, a troll purpure on a chief embattled sable a sword Or.

So we say this 7th of September, AS LIX.

why art history?

This isn’t my first runestone rodeo. A few years ago I designed a piece1 for Arnoddr’s Chiv scroll.

Nor is this my first transliteration piece. I’ve done a few, including Kolfinna’s Golden Dolphin3.

This was not my first time carving wood, or composing vocatives4.

But just because I had experience with these things didn’t mean it was going to be a retread.

The time frame of this scroll was different.

The language was different.

The materials were different.

And so, even though the subjects were familiar, I was going to have to do the reading.

One benefit of studying art history is being able to be specific. The more you know, the more context you have, and the more context you have, the better you can disambiguate between similar exemplars.

So. Let’s talk about exemplars.

stones

Like most collections, extant runestones can be sorted in myriad ways.

For at least a hundred years5, researchers have been sorting runestones, often to help shed light on the beginning of Christianity in the area by establishing their dates. During the twentieth century, they’d done this through careful, deep reading of linguistics and runes, but when these methods proved to be insufficient Anne-Sofie Gräslund published a method of characterization on stylistic grounds6.

The six categories, which overlap in time, and are pertinent throughout Sweden7, are:

(BTW, if you’re looking for data on existing runestones, Runor is a great destination. There’s a wealth of searchable data on each scroll, including inscription texts. The site is in Swedish, but if you don’t know Swedish, Google Translate is your friend.)

It’s Gräslund’s method of sorting existing runestones into these six overlapping groups which tells us most about designing our own stone.

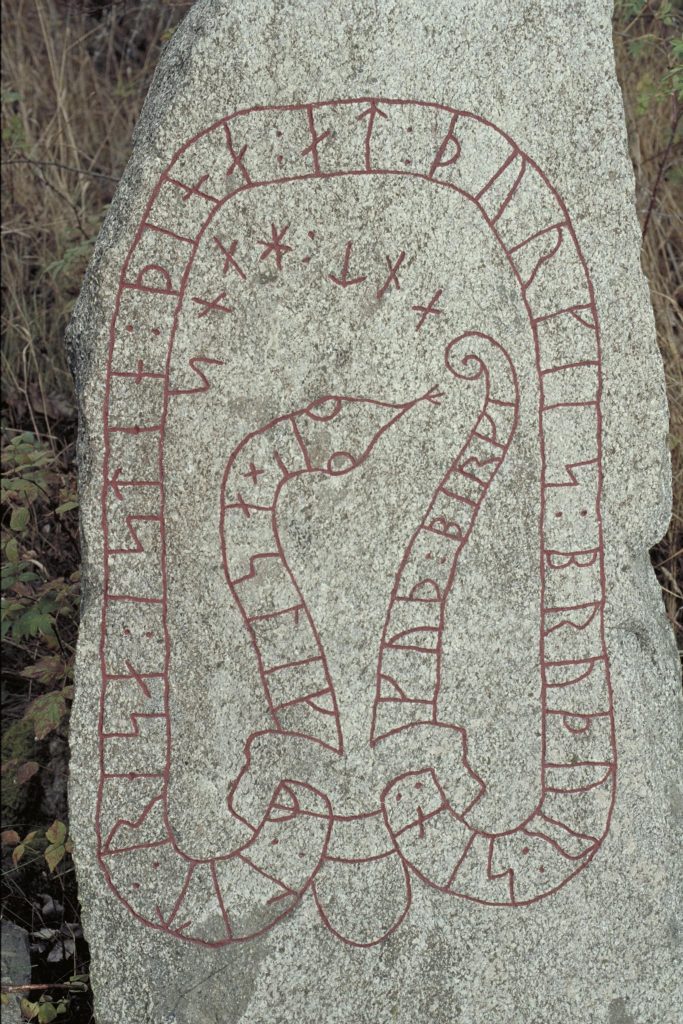

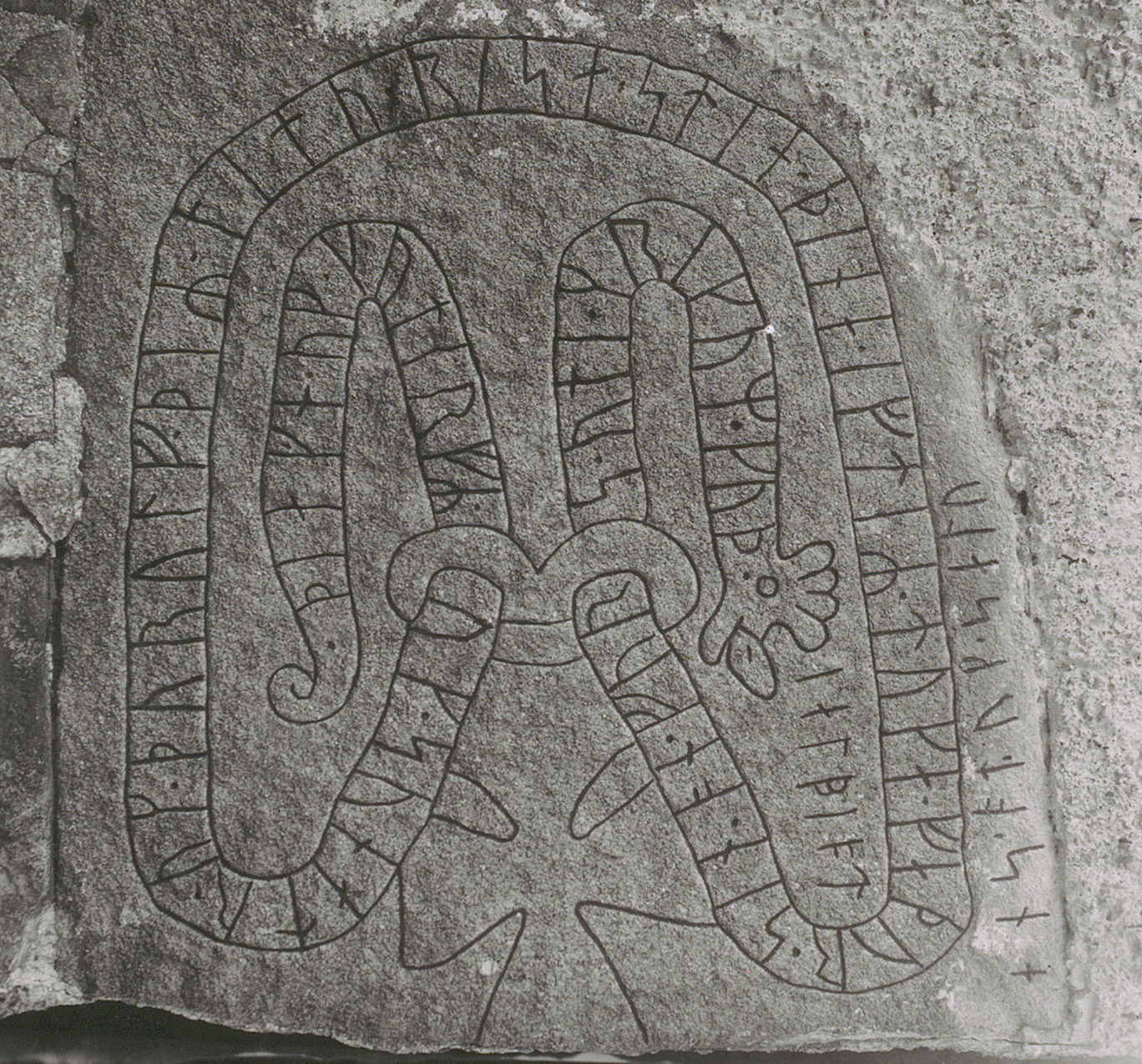

According to her system, the stylistic features of Pr1 include8:

- dense, compacted, slightly angular overall impression

- round eyes

- round ears on top of head, joined by other curls which make it look like a crown

- open mouth, with thick upper lip, sometimes crossed by a line that makes it look twisted9

- blunted lower lip

- often a rolled up tail

- no feet or extra snakes

- a curve to the overall ribbon which follows the line of the stone

- if two animals, they cross over. a single animal typically doesn’t

- presence of a union knot: generally

- presence of a cross: very frequent

- Good examples: U 32, U 160, U 201, U 276, U 324, U 430, U 611, U 785,

U 964, U 1066.

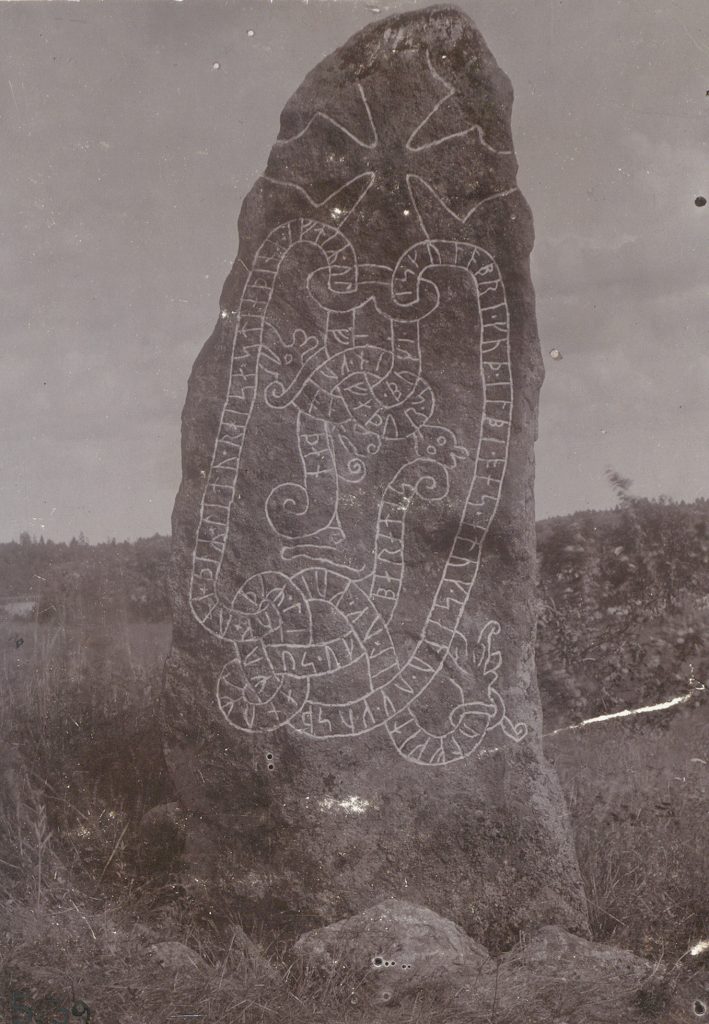

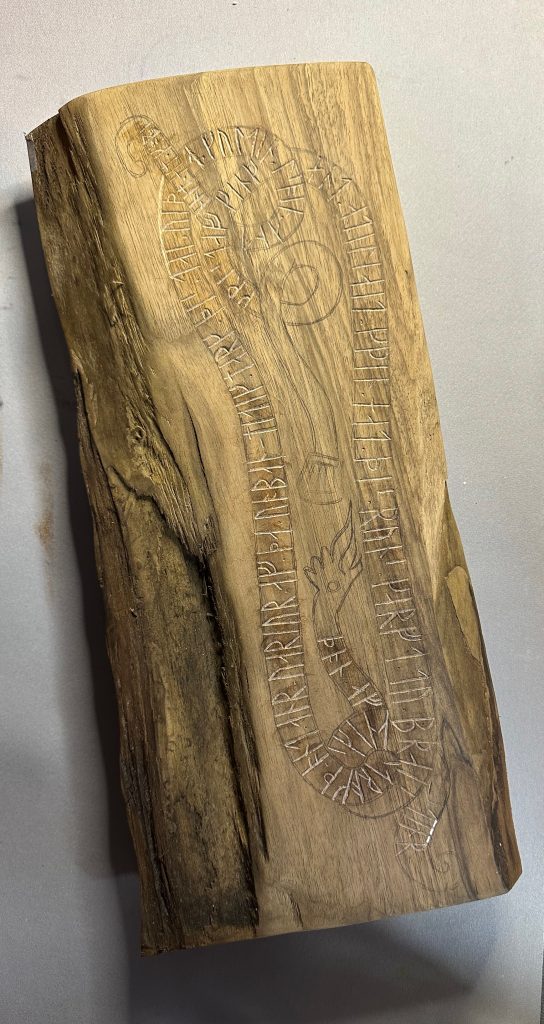

Stylistically, these features as a whole occur so frequently together that when a broken piece of carving is found, researchers confidently assume the rest of the stone will follow the same format10. My overall design was taken directly from the stone designated U 32811, chosen because its overall shape worked perfectly for my board and very little adjustment was necessary. But where change was required, I used the list above and the examples at below as a guide. Having the parameters as set by someone deeply knowledgeable about this subject area meant that I could be confident I knew what I was looking at, which then meant that I knew I was creating a runestone design that was consistent with its historical forerunners, head to tail.

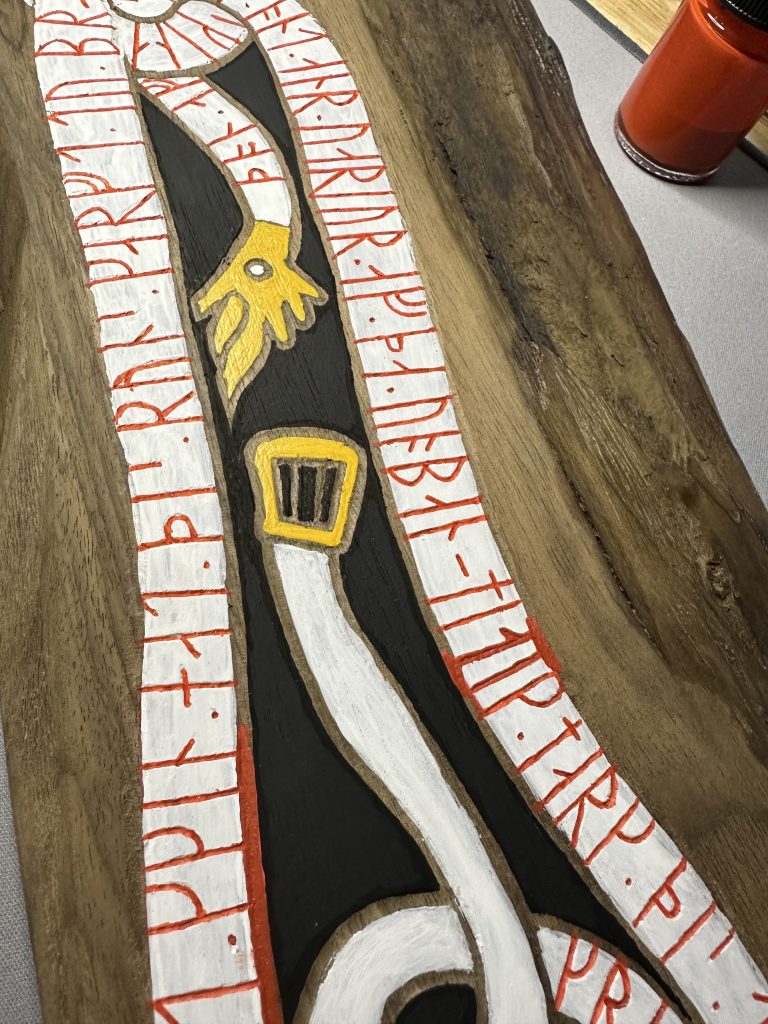

head to tail

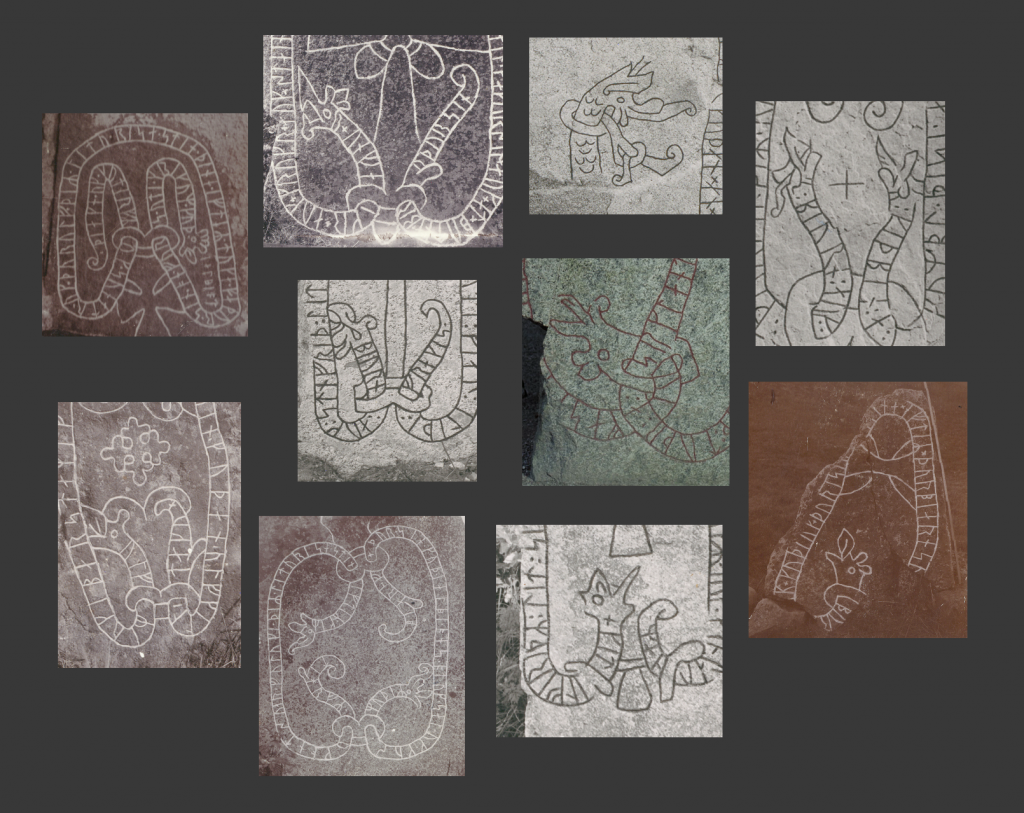

As you can see from the image of my original exemplar at right, its heads fit perfectly into the Pr1 classification with their round eyes, twisted upper and blunted lower lips, and their finger-like ears and crest. So even with the small adjustments I was making to the original designs, I wanted to make sure the result still fit within gamut.

An easy way to do that was to create an assemblage of heads from Pr1 runestones, and keep those within vision as I drew. If when I was done I cast my eyes over the assemblage and it seemed like mine would fit in, I knew the job was a good’n.

The tail was marginally easier. There seemed to be two main types with the Pr1 subset, a thumb-like C curve or a single roll, so I used one of each across the two ribbons.

buckle up

The original stone featured a large cross, as do many of this type. But since that was inappropriate for this context, I decided to take the opportunity to bring in a nod to knighthood by turning one of the ribbons into a white belt.

There were several examples of 10th–11th century buckles from Gotland (Sweden) at the British Museum. Each had a gentle outward bow at the sides, and two of three had a slight curve along the top, which provided a reliable type example. I kept the rendering abstract to fit the style; while these days we might be accustomed to art displaying realism and depth, it would be inappropriate to draw the tongue as if it rested on the outer edge, its tip eclipsing but not crossing. (It would have been something else entirely if I had chosen to treat the tongue like a snake and have it weave through other elements, but for various reasons, I decided not to do that.) The result is simple, with the appropriate visual legibility for a scroll.

And runestone legibility, evidence suggests, is helped with color.

pigment of your imagination

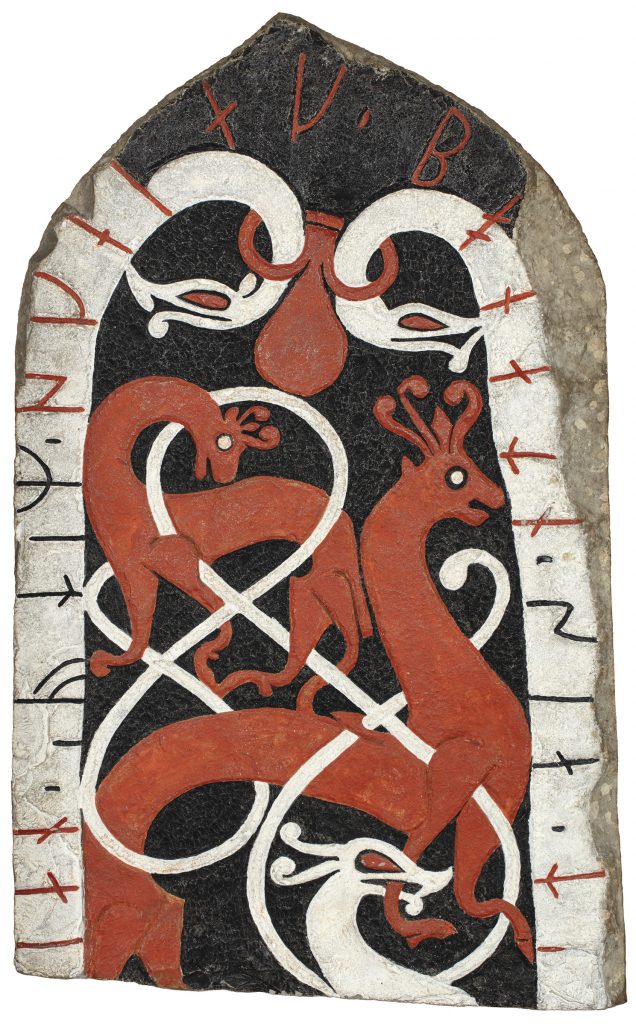

The runestones were originally painted12.

A search in the Runor or Runedata13 rune text databases for the word “paint” comes up with a large handful of Viking Age references—and that’s only when searching that single, specific word. [link] Doubtless other textual evidence exists behind different language, such as that on Sö 20614: “Here shall these stones stand, reddened with runes”. Kitzler Åhfeldt describes how the runestones at Köpingsvik church, preserved by their reuse, still retain their original pigment15. Harrison and Svensson go one step further, telling us about their red lead, their chalk, their soot and their ochre16 and their imported cinnabar17, and more. The copy of the Jelling stone displayed at the 2013 Vikings! exhibit at the National Museum of Denmark was painted in bright colors, based on traces of pigment found in the originals18. And the repainted red, black, and white Urnes-style stone found at the Resmo church, currently located at the Swedish History Museum,19 is a striking example of the visual result when color contrast is prioritized.

All this is to say that I wasn’t going to leave the carvings blank.

The runestones are predominately the red, white, and black of red lead, chalk, and soot, as mentioned above. For the yellow, I was guided by the yellow on the Jelling Stone repaint above, which, lacking access to pigment analysis, is most likely yellow ochre, but based on its intensity could also be orpiment (arsenic sulfide). Orpiment was available and commonly used for pigment until the 19th century, so it’s plausible. But again, without a test I just can’t say. You can’t judge a pigment by its color, after all20. And that’s likely even more true for runestones than it is for manuscripts.

A purple was necessary for SCA heraldic reasons, so I tried to make it as natural-pigment-y as possible by taking the saturation down. As long as it didn’t stick out too much, I was satisfied. (Just another one of those times when a historical truth has to yield to a SCAdian need.)

back to back

In fact, the heraldry side required creativity in a number of ways.

Our SCA heraldry is rooted in a very different time and style than the 10th-11th Scandinavia of this scroll. As such, it was necessary to find ways to check all the mandatory heraldic boxes, but do so within the correct world of the scroll. Sometimes when making this sort of translation it’s not hard at all to find a stylistic equivalent. And other times, it requires bending just a little bit, one way or the other.

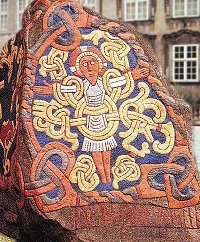

Runestones are (usually) organically shaped. And so frequently, their carvings are too. In contrast, heraldry is designed to fit in a geometric space. So I compromised; I found a frame from an existing source, by tapping in largest of the Jellling stones.

The Jelling stones are superlative for several reasons. Among other things, the largest of the grouping features the oldest depiction of Jesus in Scandinavian art [Wood 2014 p21]. Around that stone is a frame, perfect for laying out the fields of our heraldry.

As suggested above, it may seem jarring to have decoration completely fill the side of a stone board edge to edge; on the preponderance of stones, the decorations only generally follow the shape of the stone’s face. But on the largest of the Jelling stones, it’s actually possible that difference a feature of the iconography program, not a bug. According to Egon Wamers (as reported by Rita Wood21, whose word I decided to trust since Wamers’ original paper22 is in German) the layout of this carving is a nod to the manuscripts from the Christian church of Ottonian Germany, the church responsible for the conversion of the Danes.

According to Wood23, the frame could have been a direct reference to the popular religious diptychs of the time; it certainly seems as if the frame “hinges” on the corner. But due to the shape of the stone, the frame is three-cornered, whereas our heraldry needs four—both to fill the space, and also to create a legible heraldic device.

These sorts of translations are common for SCA scroll adaptations. Our needs are very different from those of the original, so it only makes sense that the forms would be different, as well. It would hardly make sense to cling slavishly to an exemplar but fail to fulfull the unique requirements of an SCA scroll…which is, or should be, our primary goal.

But this is just the framework. For its fill, I looked elsewhere.

down in trollberg

The frame wasn’t the only stylistic translation I needed to make. Both elements of heraldry, the sword and the troll, needed updates. (Or, to be more truthful, backdates.)

Rather than use a depiction of one of the monsters of Ancient and Medieval xenophobia, a Blemmye, I set out to find a good example of a Scandinavian troll. They exist throughout the literature, after all.

I chose a carving of Hyrrokkin from one of the picture stones, contemporary with our runestones.

Hyrrokkin is a female jötunn in Norse mythology. She was mentioned in several late-tenth-century poems24, and included in a hypnotic chant of troll women by an anonymous 12th century skald25:

Gjölp, Hyrrokkin | Hengikepta,

Gneip ok Gnepja | Geysa, Hála,

Hörn ok Hrúga | Harðgreip, Forað,

Hryðja, Hveðra | ok Hölgabrúðr.

Giantesses, or troll women, are more frequently and distinctly described than men in the fornaldarsögur (the literary sagas of the North)26, yet in many stories men and women trolls were of similar—sometimes indistinguishable—monstrosity27, both wearing shriveled skins for clothing28 while threatening the heroes.

Hyrrokkin is depicted above riding a wolf with a snake in each hand. Her name is a compound word, a combination of hyr (fire) and hrokkinn (curly or wrinkled)29. Together the linguistic and mythological features paint a picture of a dessicated creature, dried by fire to indistinguishability.

Given that I was adjusting the Medieval Western European troll iconography to better fit the earlier Scandinavian image of a troll, I feel like this is a successful translation. I don’t know what features of the troll inspired Stienarr to put one on his heraldry, but I hope this version fits the bill.

the point

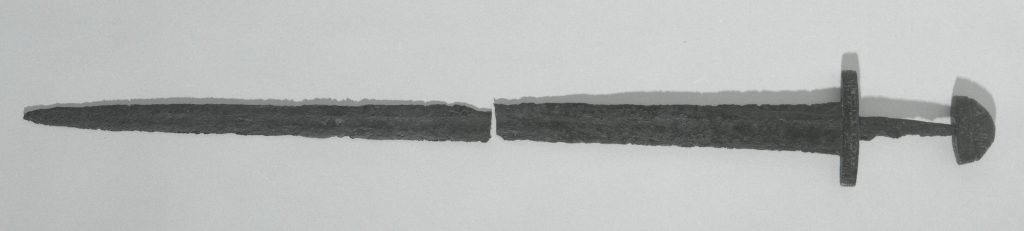

The usual sword depicted in Medieval Heraldry doesn’t particularly stand out against 10th–11th Scandinavian style. (Actually, what really seems weirdest about it and the troll above is how they’re just floating in the middle of the field, not tied into the frame. That would have better suited runestone iconography, though it doesn’t fit the rules of Medieval Heraldry.) Regardless, I prefer elements to correspond to the correct place and time, so I’m willing to do the research.

My sword has the typical domed pommel and straight guard found on a lot of Viking swords of the mid- to late-10th century, as in this Petersen Type U sword30 found in the river Lea31 and currently housed at the British Museum32.

words words words

I relish any chance to write scroll texts. Especially of the period before 1100CE.

The more you read through stone upon stone of text on Runor or Rundata[https://rundata.info/], the more a rhythm emerges:

the attribution,

the occasion,

the description.

Similarly, I had to convey my own who-what-when-why. But runestones aren’t generally…loquacious, so I had to be efficient. There were a few savory phrases I could borrow from the corpus to impart some flavor, such as “Þegn of strength”33 and kennings like “weapon-meeting”34 helped locate the poetry in a specific place and time. The word “kappi” is the equivalent of “knight” in the official list of SCA titles35, and itself comes from Cleasby and Vigfússon’s 1958 Icelandic dictionary36.

I’d hoped that when the herald read it out, all assembled could feel the echo of ages past. That’s part of the magic of the SCA.

transliteration game

Speaking of echoes of ages past, I was delighted to have a chance to once again37 play38 a happy39 game of transliteration.

The language of 10th–11th century Sweden was Old Norse, the rune set of which was the Younger Futhark. Paradoxically, the 24-character Elder Futhark of Proto-Norse diminished to 16 letters with the evolution to Old Norse, just when its number of vowels was expanding. More sounds, fewer characters. Yet none of them have as many as English, and you know how messy English is. Some sounds don’t overlap going in either direction between Old Norse and modern English, which is where our game comes in.

Transliteration is notoriously tricky. But it’s a pleasing puzzle, especially if you have experience with languages and phonetics—I like to ground my sound-symbol associations in phonetics so there’s some logic. In languages where vowel associations are ambiguous, especially older languages where we aren’t 100% sure of the pronunciation, it makes sense to plan based on the target language’s sound production. Coincidentally, it’s a similar tactic as that on the site “Orðstírr”40, whose specific thoughts on transliterating Old Norse into English I combined with Dr. Jackson Crawford’s pronunciation data and academic experience41 to create my map.

I divided vowel sounds based on their placement in the mouth. Runes weren’t doubled, so I didn’t, but diphthongs were occasionally used, so I used them when necessary. As for consonants, it was largely straightforward. I fudged “ch” to “ts”, reasoning that it would be audibly understandable in context. All “th” became Þ, whether voiced or not.

Generally the rule was simplification. I wasn’t trying to invent anything new; I was trying to efficiently use the 16 tools at my disposal.

(Yanno, efficiency. Because that’s how language and spelling always work. *cackles in Linguist*)

and so

Thank you to Mary Panesis of Tuatha for the generous donation of the live-edge reclaimed walnut board. It was beautiful to work with.

It’s always a joy to be given the opportunity to create a scroll that pushes the usual boundaries of Medieval Europe, and especially so when it can be created outside the traditional material set of SCA scrolls. Congratulations to Sir Skinna-Steinarr, and I hope when you see this on your wall, it reminds you of a wonderful day.

NOTES

- “Arnoddr’s Chivalry Scroll,” Mydwynter Studios, https://mydwynterstudios.com/arundoors-chivalry-scroll/ ↩︎

(ignore this, wordpress is terrible)↩︎- “Kolfinna’s Golden Dolphin,” Mydwynter Studios, https://mydwynterstudios.com/kolfinnas-golden-dolphin/ ↩︎

- “Lanea’s Opal,” MydwynterStudios, https://mydwynterstudios.com/laneas-opal/ ↩︎

- von Friesen 1909 ↩︎

- Anne-Sofie Gräslund, “Dating the Swedish Viking-Age Rune Stones on Stylistic Grounds,” in Runes and Their Secrets: Studies in Runology, ed. M. Stoklund, M. Lerche Nielsen, B. Holmberg and G. Fellows-Jensen. (Museum Tusculanum Press, 2006), 117–139, https://www.academia.edu/6107509/Dating_the_Swedish_Viking_Age_rune_stones_on_stylistic_grounds ↩︎

- Gräslund, _Dating,_ 130. ↩︎

- Gräslund, _Dating,_ 120. ↩︎

↩︎

↩︎- Gräslund, _Dating,_ 124. ↩︎

- “U 328,” Runor, http://kulturarvsdata.se/uu/srdb/4c816f31-d3ac-4020-89da-d3c2466e83e4. ↩︎

- “Rune Stones,” National Museum of Denmark, https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/power-and-aristocracy/rune-stones/ ↩︎

- “Rundata,” https://rundata.info/. Web client for Scandinavian Runic-text Data Base. ↩︎

- “Sö 206,” Runor, http://kulturarvsdata.se/uu/srdb/a89dd45c-403c-4740-b5cb-9f1a631ac347 ↩︎

- Laila Kitzler Åhfeldt, “The Rune Stone Fragments at Köpingsvik,” in From Ephesos to Dale- carlia. Reflections on Body, Space and Time in MedievaI and Early Modern Europe, ed. E. Regner, C. von Heine, L. Kitzler Ähfeldt, and A. Kjellström. (The Museum of National Antiquities, Stockholm. Studies I1. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 48, 2009) 83. ↩︎

- “Runestone#Colour,” Wikimedia Foundation, last modified June 11, 2024, 17:41 (UTC), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Runestone#Colour. ↩︎

- Kristina Ekero Eriksson and Dick Harrison, Vikingaliv (Natur & Kultur, 2017) 209. One page of which (in Swedish) can be read at https://www.google.com/books/edition/Vikingaliv/Pto2DwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&pg=PA209&printsec=frontcover. The pertinent passage translates via Google to, “chemists have been able to analyze traces of color: in one case, traces of bright red cinnabar, an exclusive import pigment, were found, but otherwise lead and iron oxide red dominate.” ↩︎

- “Jelling_stones#Modern_copies_of_the_runestone_of_Harald_Bluetooth,” Wikimedia Foundation, last modified May 18, 2024, 21:06 (UTC), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jelling_stones#Modern_copies_of_the_runestone_of_Harald_Bluetooth. ↩︎

- “Runestone,” Swedish History Museum. https://samlingar.shm.se/media/75FC0E39-DB58-4CAC-B4B4-9042784CA1C3. Also located on Runor with the signum Öl Fv1911;274B at http://kulturarvsdata.se/uu/srdb/e77158d7-b52b-43ec-a16e-aa083d768b30. ↩︎

- Cheryl A. Porter, “You Can’t Tell a Pigment by Its Color,” in Making the Medieval Book. Techniques of Production, 1995, 111–16. ↩︎

- Rita Wood, “The Pictures on the Greater Jelling Stone,” Danish Journal of Archaeology 3 (May 1, 2014): 19, https://doi.org/10.1080/21662282.2014.929882. ↩︎

- Egon Wamers, … “… Ok Dani Gærði Kristna … Der Große Jellingstein Im Spiegel Ottonischer Kunst,” Frühmittelalterliche Studien 34, no. 1 (2000), 132. ↩︎

- Wood, Pictures, 27–28. ↩︎

- John Lindow, Norse Mythology : A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs ( Oxford University Press, 2001) 196–197. ↩︎

- Elena Gurevich, ‘”Anonymous, Trollkvenna heiti” in Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3, ed. K. E. Gade and E. Marold. (Brepols, 2017), 723. https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=3185. ↩︎

- Aðalheiður Guðmundsdóttir, “Behind the Cloak, between the Lines: Trolls and the Symbolism of Their Clothing in Old Norse Tradition,” European Journal of Scandinavian Studies, (January 1, 2017), 331, https://www.academia.edu/35257514/Behind_the_cloak_between_the_lines_Trolls_and_the_symbolism_of_their_clothing_in_Old_Norse_tradition. ↩︎

- Guðmundsdóttir, _Cloak,_ 332, 334 ↩︎

- Guðmundsdóttir, _Cloak,_ 332–336 ↩︎

- Lindow, _Norse Mythology,_ 196 ↩︎

- “Swords,” The Viking Age Compendium, https://www.vikingage.org/wiki/wiki/Swords. ↩︎

- Bjørn, Anathon and Haakon Shetelig, Viking Antiquities in Great Britain and Ireland (H. Aschehoug, 1940), 60, https://archive.org/details/vikingantiquitie04scie/page/60/mode/1up. ↩︎

- “Sword,” British Museum, https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1915-0504-1. ↩︎

- “Sö 90,” Runor, http://kulturarvsdata.se/uu/srdb/4794814b-0795-4892-92df-21d7abc4a473. ↩︎

- Martin Chase (ed.), “Einarr Skúlason, Geisli 29″ in Margaret Clunies Ross (ed.), Poetry on Christian Subjects. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 7. (Brepols, 2007) 30-1, https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=verse&i=2059&v=i. ↩︎

- “The List of Alternate Titles | Viking Icelandic,” SCA Heraldry, https://heraldry.sca.org/titles.html#Viking%20Icelandic. ↩︎

- Richard Cleasby and Guðbrandr Vigfússon. An Icelandic-English Dictionary, 2nd ed. (Clarendon, 1957), http://www.germanic-lexicon-project.org/html/oi_cleasbyvigfusson/b0331.html. ↩︎

- “Lanea’s Opal,” Mydwynter Studios, https://mydwynterstudios.com/laneas-opal/. ↩︎

- “Kolfinna’s Golden Dolphin,” Mydwynter Studios, https://mydwynterstudios.com/kolfinnas-golden-dolphin/. ↩︎

- “Suphunibal rabat bat Abdeshmun: Laurel,” Meisterin Kolfinna Valravn, https://sites.google.com/view/kvalravn/scribe/2022/08-laurel-suphunibal-rabat-bat-abdeshmun. ↩︎

- “Younger Fuþark Vowels ᚢ u, ᛁ i, and ᛅ a,” Orðstírr, https://ordstirr.wordpress.com/runes/younger-futhark-vowels-%E1%9A%A2-u-%E1%9B%81-i-and-%E1%9B%85-a/ ↩︎

- “Writing English in Runes,” YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A271ohcO7Yc. ↩︎

- “All About The Futhark(s)”, Scandinavian Archaeology, https://www.scandinavianarchaeology.com/all-about-the-futharks/. ↩︎

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Cleasby, Richard and Guðbrandr Vigfússon. An Icelandic-English Dictionary. 2nd ed. Clarendon, 1957. http://www.germanic-lexicon-project.org/html/oi_cleasbyvigfusson/b0331.html.

Eriksson, Kristina Ekero, and Dick Harrison. Vikingaliv. Natur & Kultur, 2017.

Fuglesang, Signe Horn. Some Aspects of the Ringerike Style: A Phase of 11th Century Scandinavian Art. Odense University Press, 1980. http://archive.org/details/someaspectsofrin0000fugl.

Fuglesang, Signe Horn. “Swedish Runestones of the Eleventh Century: Ornament and Dating.” In Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung: Abhandlungen des Vierten Internationalen Symposiums über Runen und Runeninschriften in Göttingen vom 4.-9. August 1995 / Proceedings of the Fourth International Symposium on Runes and Runic Inscriptions in Göttingen, 4-9 August 1995, edited by Klaus Düwel, 197–218. De Gruyter, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110821901.197.

Gräslund, Anne-Sofie. “Dating the Swedish Viking-Age Rune Stones on Stylistic Grounds.” In Runes and Their Secrets: Studies in Runology, edited byEdited by Marie Stoklund, Michael Lerche Nielsen, Bente Holmberg, and Gillian Fellows-Jensen. Museum Tusculanum Press, 2006. https://www.academia.edu/6107509/Dating_the_Swedish_Viking_Age_rune_stones_on_stylistic_grounds

Graham-Campbell, James, Signe Horn Fuglesang, Ingmar Jansson, and Helen Clarke. “Viking Art.” In Oxford Art Online: Grove Art Online. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

Gurevich, Elena. ‘”Anonymous, Trollkvenna heiti.” Poetry from Treatises on Poetics. Skaldic Poetry of the Scandinavian Middle Ages 3, edited by Kari Ellen Gade and Edith Marold. Brepols, 2017. https://skaldic.org/m.php?p=text&i=3185.

Kitzler Åhfeldt, Laila. “The Rune Stone Fragments at Köpingsvik.” In From Ephesos to Dalecarlia. Reflections on Body, Space and Time in Medieva I and Early Modern Europe, edited by E. Regner, C. von Heine, L. Kitzler Ähfeldt, & A. Kjellström. The Museum of National Antiquities, Stockholm. Studies I1. Stockholm Studies in Archaeology 48, 2009. https://www.academia.edu/3445233/The_Rune_Stone_Fragments_at_K%C3%B6pingsvik.

Lindow, John. Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press, 2001.

Porter, Cheryl A. “You Can’t Tell a Pigment by Its Color.” In Making the Medieval Book. Techniques of Production, 1995.

Evighetsrunor.”Runor.” https://app.raa.se/open/runor/search.

Wilson, David M. “The Development of Viking Art.” In The Viking World. Edited by Stefan Brink with Neil Price, 323–338. London: Routledge, 2008.

Wood, Rita. “The Pictures on the Greater Jelling Stone.” Danish Journal of Archaeology 3 (May 1, 2014), https://doi.org/10.1080/21662282.2014.929882.