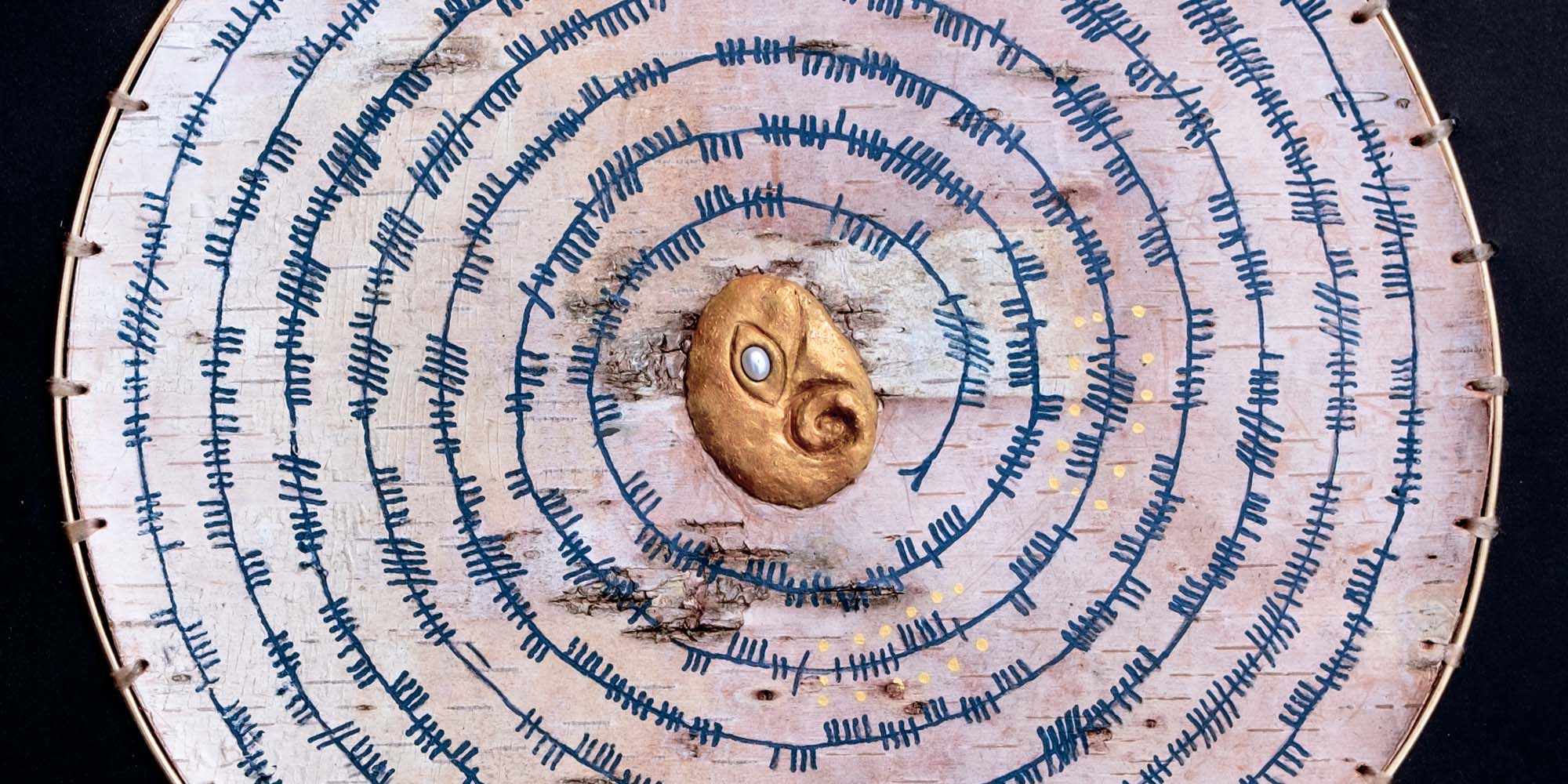

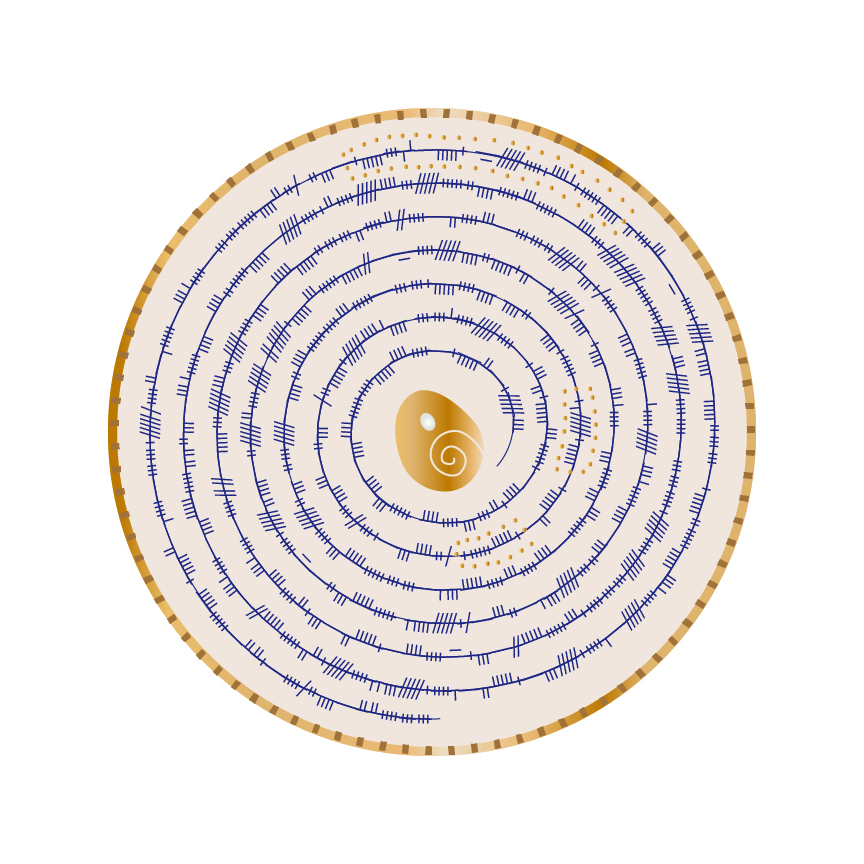

Scroll honoring Lady Anubh na Preachain being granted the Order of the Pearl. Words, design, and production by me.

Well-come all in | and be warmed by the wisdom

of Anubh Na Preachain. | Let Pearls now anoint

her heart and hearth, | heralding the skill

of this coin-reader, | curiosity-currier,

tree-wearer, | weaving tapes and tales.

The egg nurtures knowledge.

Let word-fame fly her | this fourth of March

into Pearl’s Order, | granting personal arms

as the 57th winter | of our society wanes.

So say Abran and Anya, | most august of monarchs

where Atlantia salutes | its science and art.

when is a hat not a hat?

It is always a twofold blessing/challenge to create a scroll for a persona when and where there is no written culture to emulate. It requires creativity, knowledge of many techniques, flexibility, and understanding of a myriad of materials.

But if not making a page-based scroll, it is also not always appropriate—or desired, whether on behalf of maker or recipient—to create a whole-ass object either.

A scroll is foremost a gift, so while I wanted to create a scroll object, I knew Anubh would appreciate something low maintenance, nothing that needed dusting. Therefore I needed to keep the entire thing flat enough to be framed behind glass.

Anubh has done a magnificent job researching, experimenting with, and creating Iron Age birch bark hats, and I wanted to celebrate them. But I needed to do it…flatly. So instead of an actual hat, I began with a circle, echoing the appearance of a hat from above. A reference to a hat, rather than a hat itself.

Because this scroll replicates neither a manuscript nor an exact artifact, it was even more important that it have a “resonance of the spirit”, as it were. Resonance with the place and time period, and resonance with the recipient. And that started with the materials.

material culture

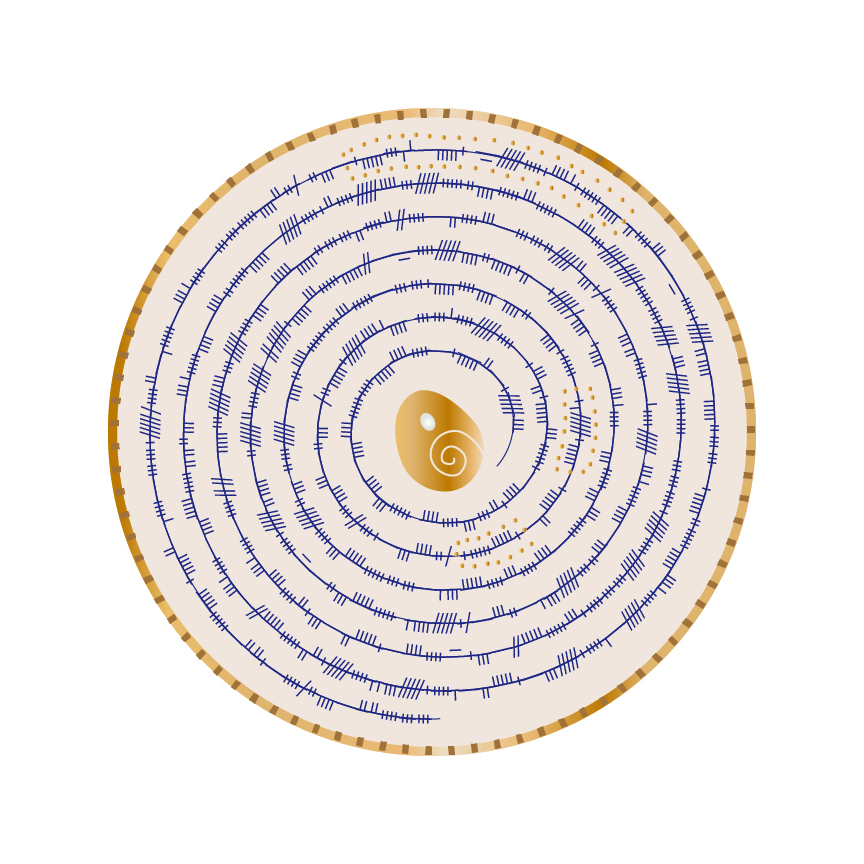

The circle is made of birch bark, flattened in the manner described in her research, with a few amendments for my specific workspace situation and resources.

(Have I since bought a garment steamer? Yes. Did I have one for this project? No. Did I wish I did? Many times. 😅)

I used bronze wire to bind the edge instead of the cane she used, a substitution made to add a little bit of bling. Then the whole shebang was attached to the backing board using artificial sinew with the double needle technique I often use in leatherworking, reasoning that it would provide the required stability and even pull for which I use it with leather.

who’s the boss

Her OP entry listed no registered heraldry, which left me open to other personal iconography within the design.

The heraldic oyster shell wouldn’t come into being for centuries. As I learned in the research for Runa’s Pearl, the only native British oyster is Ostrea edulis, or the European flat oyster, therefore its natural shapes roughly dictate what was appropriate for a shell at this time. (Understanding, of course, that this was a period of widespread abstraction in art, so I had a little leeway.)

In addition, Anubh means “the egg” in Gaelic, and she has a tattoo and personal sigil representing a spiral-graced egg. This provided a perfect jumping off point; there is a lot of visual overlap between her sigil and a representation of an European flat oyster with a pearl, both in the outer shape and the inner ridges of detail.

Between the organic topography of the birch bark, the constraints of the (ornery, recalcitrant, and stubborn) clay, and the overarching need to keep the scroll as framable as possible, there were considerable design restrictions. So in lieu of the classic concave shell I chose to try carving downward—in effect making a gently domed egg-shaped and shell-like boss for the center of the circle.

But what to carve?

plastic style

The Plastic Style is a classification of La Tène art typified by high relief. When Jacobsthal first described the style in 1944, he highlighted how it elides the distinction between the ornament and the object. “Cut off the spirals and you cut into the flesh.”1 Not simply laid overtop, the decoration is the item.

I consulted a number of Plastic Style artifacts in the design of this boss. The linchpin seen below at left seemed a particularly good reference, not only for its lentoid shape but for its shell-like, curvilinear decoration. The same treatment of the main three dimensional spiral—the spiral that looks like it would be a fun slide at a water park—can also be found on the Bulgarian chariot fitting seen at middle.

In addition, the guide ring gave me direction for the way to integrate the pearl, as did the Stanhope Armlet (at right). The latter in particular seems to form the shape of an eye…a visual riddle, so frequent in La Tène art.

masks

One of the wonderful things about La Tène art is its frequent sense of play, which often comes in the form of hidden—and abstract—beasts or faces.

The lentoid (or almond shaped) element on this guide ring looks like an eye, because it is an eye. If we flip it ninety decrees clockwise, we can trace a stylish half of a face with a slicked-back hairstyle.

And again, the same can be done with the chariot fitting shown above. Flip it upside down, and it’s clearly some sort of video game Princess Lea. She’s even got nostrils.

A sense of play within a design is a motif which carries forward for centuries to come. It’s this sense of play, this a doubled meaning, that made me aim to represent both Anubh’s egg and an oyster shell at the same time.

This was my first time trying to sculpt anything in the Plastic Style, let alone in this particular clay, and it won’t be the last. I look forward to refining the technique to explore more design possibilities

gold and bronze glinting in the firelight, nestled against wool and woad, deep within the canopy of trees

spirit through color

Blue, birch, and gold.

Woad blue seemed an obvious choice (although done in gouache, not woad). And the jeweler’s bronze wire looks more golden than the reddish bronze more typical of the metalwork of the period, so the boss needed to look like more like gold.

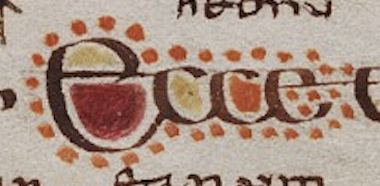

Alongside the main elements—golden wire, bark, blue letters—I also added gold dots to set off the names, taking a cue from the “dotted contours” which highlight initials and details in Insular manuscripts made several hundred years later. This decoration, this bright highlight, underscores how people are the most important elements of the award.

The richness of gold set against the roughness of bark and the matte blue of woad embodies the spirit of Celtic Iron Age bling. Having played in the context of said bling (along with Anubh) for twenty years, these colors and textures feel correct. And for a scroll object which doesn’t reproduce a specific artifact but instead seeks to express the spirit of a place/time, that authenticity of lived experience is even more important than it would have been otherwise.

the words

As discussed in my writeup of Lanea’s Opal, we don’t have an accurate system of writing for this place and time. We could steal one from a different culture, but that would really not be in the correct spirit. So once again I used transliterated Ogham; it’s a few centuries too late for La Tène, but the spirit is truer.

The words themselves are loosely inspired by Old English poetry, both because I know she really likes using alliteration in her work and also because it’s a well-documented verse form which suits itself well to the sort of declarative and alliterative feel I wanted. (Since we don’t have accurate poetry to reference, I could have entirely invented the form, but I preferred some guide rails. Even if they’re not from the exact place and time.)

Using a riddle also gave me a chance to weave in some wordplay alongside the more serious job of telling who-what-when-where-why; the sense of play in Plastic Style art seems a cousin to the sense of play in Old English riddles. “Tree-wearer” refers to her birchbark hats, “weaving tapes and tales” refers to her belts and her bardic work.

“The egg nurtures knowledge” specifically reminded me of self-contained half lines like the one which begins riddle 47 from the Exeter book:

Moððe word fræt. Me þæt þuhte

wrætlicu wyrd, þa ic þæt wundor gefrægn,

þæt se wyrm forswealg wera gied sumes,

þeof in þystro, þrymfæstne cwide

ond þæs strangan staþol. Stælgiest ne wæs

wihte þy gleawra, þe he þam wordum swealg.

A moth ate words. That seemed to me

a curious happening, when I heard about that wonder,

that the worm, a thief in the darkness, swallowed

a certain man’s song, a glory-fast speech

and its strong foundation. The stealing guest was not

at all the wiser for that, for those words which he swallowed.

The introductory phrase, “moððe word fræt” translates to “a moth ate words” The brevity and of the statement, placed as it is among a sea of long phrases and clauses, make it feel intentionally clear, forceful, and important. “The egg nurtures knowledge”.

In our case, its placement at the end of a verse about her work makes it into a conclusion: Anubh’s teaching is woven throughout her work.

I was delighted to create this art for Anubh, and celebrate that she is now in the Order of the Pearl. Those of us who have been privileged to know her for decades, who have been witness to her passion for creativity, her skill at storytelling, and her facility with teaching, can only be chuffed to bits that finally others are seeing it all, too.

further reading

Cone, Polly. Treasures of Early Irish Art: 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1977. Published following the travelling exhibition of the same name.

Farley, Julia and Fraser Hunter, eds. Celts, art and identity. London: The British Museum Press, 2015.

Harding, Dennis. The Archaeology of Celtic Art. London and New York: Routledge, 2007.

1Jacobsthal, P. Early Celtic Art. v. 1. Clarendon Press, 1944.

Kruta, Vinceslas. Celts: History and Civilization. London: Hatchette Illustrated UK, 2005.

Megaw, Ruth and Vincent Megaw. Celtic Art. New York: Thames and Hudson Inc, 1989 and 2001.

Zaczek, Iain. The Art of the Celts. London: Parkgate Books Ltd, 1997.